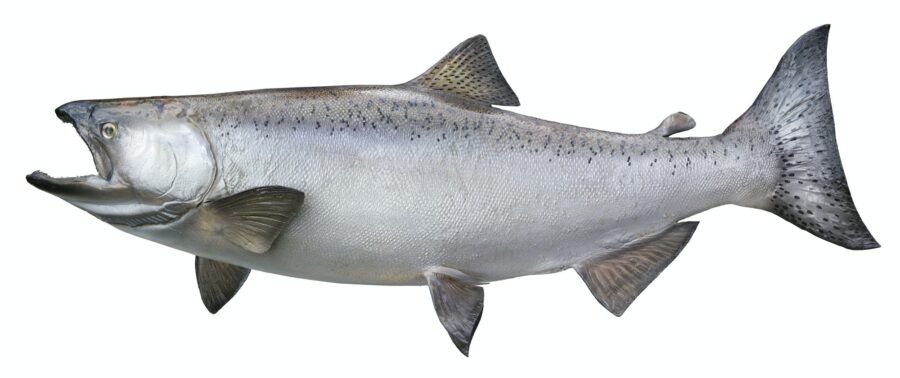

King/Chinook Salmon [Oncorhynchus tshawytscha].

Northwest’s Salmon Population May Be Running Out of Time

The Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office found that some salmon species are “on the brink of extinction.” Habitat loss, climate change and other factors are to blame, it said.

A Washington State report put it bluntly:

Because of the devastating effects of climate change and deteriorating habitats, several species of salmon in the Pacific Northwest are “on the brink of extinction.”

Of the 14 species of salmon and steelhead trout in Washington State that have been deemed endangered and are protected under the Endangered Species Act, 10 are lagging recovery goals and five of those are considered “in crisis,” according to the 2020 State of Salmon in Watersheds report, which was released last week.

“Time is running out,” said the report, which is produced every other year by the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office. “The climate is changing, rivers are warming, habitat is diminishing, and the natural systems that support salmon in the Pacific Northwest need help now more than ever.”

Before the 20th century, an estimated 10 million to 16 million adult salmon and steelhead trout returned annually to the Columbia River system. The current return of wild fish is 2 percent of that, by some estimates.

One of the largest factors inhibiting salmon recovery is habitat loss, Mr. Neatherlin said. A growing human population has led to development along the shoreline, and the addition of bulkheads, or sea walls, that encroach on beaches where salmon generally find insects and other food. More pavement and hard surfaces have contributed to an increase in toxic storm water runoff that pollutes Puget Sound.

More than 20,000 barriers — including dams, roads and water storage structures — block salmon migration paths in Washington alone, according to the state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The waters they swim in are warming — in 2015, unusually warm water killed an estimated 250,000 sockeye salmon — and there is less cold water to feed streams in the summer, the report said, because slowly rising temperatures have accelerated the melting of glaciers. . . .

Why Remove The 4 Lower Snake River Dams?

The Four Lower Snake River Dams: Lower Granite Dam [miles 107.5], Little Goose Dam [miles 70.3], Lower Monumental Dam [miles 41.6], Ice Harbor Dam [miles 9.7]. Army Corps of Engineers, Walla Walla District.

The Northwest would not be what it is today without hydroelectricity from the region’s dams. Yet one simple fact remains: not all dams are created equal. Below is a list of commonly asked questions about Columbia and Snake River salmon and the four lower Snake River dams with answers from regional stakeholders. Check out the Myths & Facts page.

The Northwest would not be what it is today without hydroelectricity from the region’s dams. Yet one simple fact remains: not all dams are created equal. Below is a list of commonly asked questions about Columbia and Snake River salmon and the four lower Snake River dams with answers from regional stakeholders. Check out the Myths & Facts page.