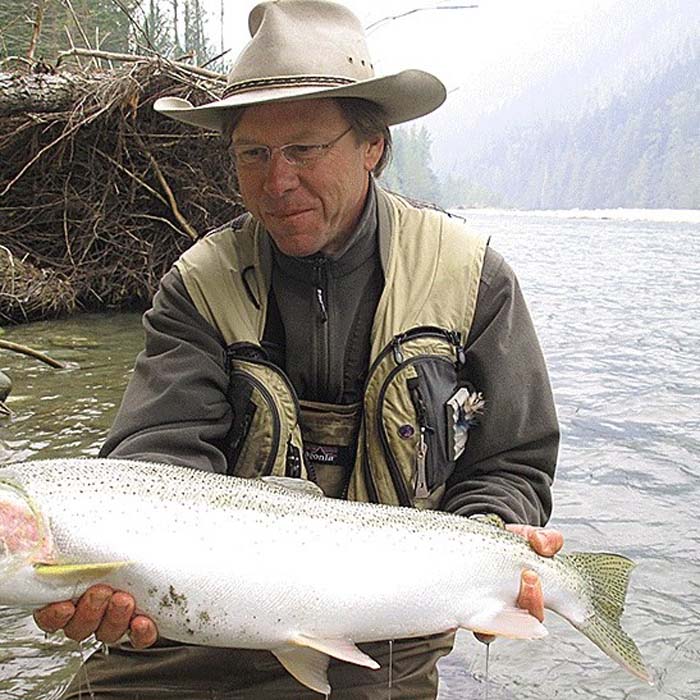

Guido Rahr, the patron saint of wild salmon, holding a supplicant he releases. Rahr was the driving force that launched the Wild Salmon Center and now one of 20 volunteer Board of Directors, which includes experts in international conservation, salmon research and management from Russia, Canada, and the United States. PHOTO courtesy of Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. The 20th century was not kind to Pacific salmon. Dams on rivers throughout Washington and Oregon blocked fish from their spawning grounds, agriculture turned rivers like California’s San Joaquin into muddy trickles, and mismanaged fisheries across the Pacific Rim harvested salmon at unsustainable rates. To compensate for the resultant declines, hatcheries released billions of fish into rivers throughout the Northwest, overwhelming wild populations and diluting genetic diversity.

Was there another author who could write as rivitingly as Laura Hillenbrand?

By Skip Clement

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]aura Hillenbrand had defined for readers young and old, literati and couch potatoes, and me what the word “riveting” meant. You did not have to be a college graduate to fall in love with Hillenbrand’s brand of word parsing. Even if the reader relied on their index finger, they could enjoy anything Hillenbrand wrote, and understand it.

Saving wild salmon, the passion of one man – his inspiring and compelling story needed to be told

As young cousins, author Tucker Malarkey and Portland salmon conservationist Guido Rahr spent summers together at their families’ cabins on the Deschutes River, where Rahr exhibited a precociousness with nature and independence that astonished and sometimes concerned his outdoorsy family. Rahr sometimes allowed the younger Malarkey to tag along as he explored and captured reptiles but never took much interest in her or anyone else. “Having a normal conversation with him was pointless,” Malarkey writes in her first book of nonfiction, “and I never tried. It was by following him that I learned.” — Scott F. Parker | For The Oregonian/OregonLive. Photo Tucker Malarkey.

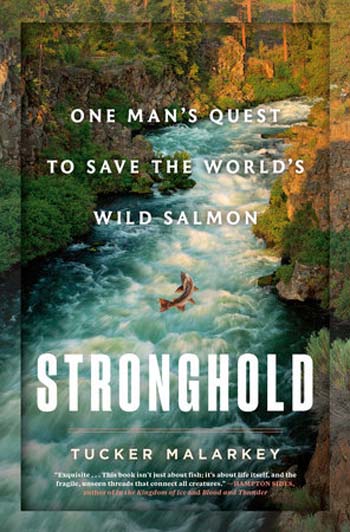

Tucker Malarkey’s book titled Stronghold: One Man’s Quest to Save the World’s Wild Salmon are the summary of the journey a willing reader gets to take. There’s isn’t a sentence in the book that the writer strays from her first cousin Guido Rahr’s life long passion for salvaging salmon of the Pacific Rim. He is seemingly Asperger-like and driven as if his own survival is tied to the salmons’.

- Rahr has spent his life trying to understand and preserve what’s left of the world’s Wild Salmons. He is fully aware of what we immigrants here in the Northeastern Americas almost succeeded in doing – extincting the Atlantic salmon in most thoughtless and greedy ways.

So, when I’d gotten only a few pages into Tucker Malarkey’s STRONGHOLD, I realized someone could write as well a Hillenbrand. Make a sentence forcing me to read it over and over in pure disbelief and wonderment. I had a love affair with wordsmithing extraordinaire, again.

So, I’m guessing you think I liked the read?

I did and am probably too easily influenced by the environmental aspects of the great outdoors when and if gamefish, especially salmons, steelhead, stripers, bonefish and tarpon are visible through my looking glass.

Here’s an excerpt from the author’s thoughts on her book about her first cousin whom she grew up with spending summers traipsing North America’s west coast forests and salmon rivers

Here’s an excerpt from the author’s thoughts on her book about her first cousin whom she grew up with spending summers traipsing North America’s west coast forests and salmon rivers

I remember the moment I sat up and took notice of the risks my cousin Guido Rahr was taking for fish — the same moment I started taking notes about his adventures, notes that would one day become a book. We were sitting in the grass outside our family fishing cabins on the Deschutes River where, since childhood, we had enjoyed days of wilderness and unbroken conversations. Our regular returns to the Deschutes marked our family’s time and highlighted the twists and turns of our personal journeys. Guido’s had long been the most surprising. A born hunter, he had spent his childhood stalking the high desert for snakes and lizards. Then it became fish, and his hunting ground expanded from the Deschutes to the entire Pacific Northwest. Guido pursued salmon all the way to Alaska and became one of the world’s finest fly fisherman. It was when these magnificent fish began to disappear from Oregon’s rivers that he converted his skills for catching wild creatures to humans.

This unlikely outlier has since galvanized a small army of well-placed people to protect the habitat he dearly loves

Guido was assembling his fly-fishing gear while giving me the latest update on his crusade to protect the best salmon rivers across the Pacific Rim, rivers he calls “strongholds” for the safety they offer this invaluable species as their numbers across the region decline. Like many hunters, Guido is a dedicated conservationist, for hunting grounds need protection. Guido has achieved a great deal with his stronghold mission and, against all odds, the Pacific Rim is dotted with protected areas and rivers that he and his organization, the Wild Salmon Center, have fought for from Northern California to the Russian Far East. But the future of Russia’s salmon is still uncertain — and the country is home to 40% of the world’s wild salmon. If he can’t protect Russian fish, his stronghold strategy will fail.

He told me now he’d just returned from Moscow. Years of hammering away at Russia’s district and regional governments and agencies had won him both local partnership and protection for some of Kamchatka’s finest salmon rivers. But Russia was poised for rampant development in the far east, and Guido knew of plans to drill, excavate, and clear-cut the pristine region — which spelled disaster for the salmon. At this juncture, he needed to reach the people in control of such development, or those who had the resources to stop it. He needed the support of Russia’s most powerful men.

Under the surface, he was still an obsessive hunter, and he had set his sights on the most challenging and mysterious quarry to date

He told me that through one of his high-level connections, he’d just met with the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska and asked directly if he would help protect Russia’s salmon. The story alarmed me. I had studied Soviet Russia in college and knew something of the dark complexities of its power elite.”

Did Guido know what he was doing? . . .

Featured Image from Wild Salmon Center – photo by Igor Shpilenok – ЦЕНТР ДИКОГО ЛОСОСЯ.

Join the discussion 2 Comments