Adult Atlantic Salmon [Salmo salar] by Thom Glace, award winning watercolorist, dedicated fly fisher, and conservationist.

Atlantic salmon [Salmo salar] quick facts:

- Only farm-raised Atlantic salmon are found in U.S. seafood markets.

- Commercial and recreational fishing for Atlantic salmon in the United States is prohibited.

- Gulf of Maine’s distinct population segment (DPS) of Atlantic salmon is protected under the Endangered Species Act.

- There are three groups of Atlantic salmon: North American, European, and Baltic.

- The three groups of Atlantic salmon are found in the waters of North America, Iceland, Greenland, Europe, and Russia.

About the Species:

Atlantic salmon, also known as the “King of Fish,” are anadromous, which means they live in fresh and saltwater. Atlantic salmon have a complex life history that begins with spawning and juvenile rearing in rivers. They then migrate to saltwater to feed, grow, and mature before returning to freshwater to spawn.

Atlantic salmon are vulnerable to many stressors and threats, dams and culverts that block or impede the migratory movements between freshwater spawning and rearing habitats and the marine environment, habitat degradation, foreign fisheries, and poor marine survival. They are considered an indicator species or a “canary in the coal mine.” This means that the health of the species is directly affected by its ecosystem health. When a river ecosystem is clean and well-connected, its salmon population is typically healthy and robust. When a river ecosystem is not clean or well-connected, its salmon population will usually decline.

Atlantic salmon in the United States were once native to almost every coastal river northeast of the Hudson River in New York. But dams, pollution, and overfishing reduced their population size until the fisheries closed in 1948. Commercial and recreational fishing for wild sea-run Atlantic salmon is still prohibited in the United States. As a result, all Atlantic salmon in the public market is cultured and commercially grown. Currently, the only remaining wild populations of U.S. Atlantic salmon are found in a few rivers in Maine. These remaining populations comprise the Gulf of Maine distinct population segment, which is endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Some populations in southern Canada and Europe are also declining significantly, creating concern about the status of this species globally. In addition, the Gulf of Maine DPS is one of eight Species in the Spotlight. This means that NOAA Fisheries has prioritized focusing recovery efforts on research to better understand the major threats and stabilize the Gulf of Maine DPS by improving access to quality habitat and thus, preventing its extinction.

Our dedicated scientists and partners use a variety of innovative techniques to conserve Atlantic salmon and to protect and rebuild depleted endangered populations. NOAA Fisheries also works with partners to protect federally designated critical habitat for Atlantic salmon and makes every effort to engage the public in conservation efforts.

Population Status:

Adult Atlantic salmon – ESA Endangered. Gulf of Maine DPS

Worldwide, Atlantic salmon populations among individual rivers can range considerably. Atlantic salmon returns to rivers in Northern Europe can exceed nearly a quarter-million in some years. However, some populations are small, numbering in the low hundreds or even single individuals.

The endangered Gulf of Maine DPS of Atlantic salmon has declined significantly since the late 19th century. Historically, dams, overfishing, and pollution led to large declines in salmon abundance. Because of this, the commercial Atlantic salmon fishery closed in 1948. Improvements in water quality and stocking from hatcheries helped rebuild populations to nearly 5,000 adults by 1985. But dams continued to block access to habitats and marine survival has decreased significantly since the late 1980s, resulting in annual returns to the United States of generally less than 1,000 adults. The rapid decline and dire status of the ESA-listed Gulf of Maine DPS makes it a priority for NOAA Fisheries and partners to prevent its extinction and promote its recovery.

Appearance:

While in freshwater, young Atlantic salmon—known as parr—have brown to bronze-colored bodies with dark vertical bars and red and black spots. These markings camouflage and protect them from predators. Once young salmon are ready to migrate to the ocean, their appearance changes; their vertical barring disappears and they become silvery with nearly black backs and white bellies. When adults return to freshwater to spawn, they are very bright silver. After entering the river, they will again darken to a bronze color before spawning in the fall. After spawning, adults—now called kelts—can darken further and are often referred to as black salmon. Once adults return to the ocean, they revert to their counter-shaded coloration dominated by silver.

First ever salmon for Christophe Thiffault, which he released on the Matapedia River, Canada, this summer [2022] and estimated to weigh 32-pounds. Photo ASF/CGRMP.

Typically, an Atlantic salmon returning to U.S. waters will be 4 years old, having spent 2 years in freshwater and 2 years at sea. These fish are called “two sea winter fish,” or 2SW, and are usually 28 to 30 inches long and 8 to 12 pounds. The size of adults returning to freshwater from the ocean depends on how long they lived at sea. Young salmon returning to freshwater after 1 year at sea (known as “grilse” or 1SW) are smaller than 2SW adults. Adult salmon can migrate several times to spawn—a reproductive strategy known as iteroparity—though repeat spawners are becoming increasingly rare.

Behavior and Diet:

Atlantic salmon are migratory. They travel long distances from the headwaters of rivers to the Atlantic Ocean before returning to their natal rivers. For example, U.S. salmon leave Maine rivers in the spring and reach the seas off Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, by mid-summer. They spend their first winter at sea south of Greenland and their second growing season at sea off the coast of West Greenland and sometimes East Greenland. Maturing fish travel back to their native rivers in Maine to spawn after 1 to 3 years.

The diet of Atlantic salmon depends on their age. Young salmon eat insects, invertebrates, and plankton. The preferred diet of adult salmon is capelin. Capelin (similar in appearance to rainbow smelt) are elongated silvery fish that reach 8 to 10 inches in length.

Where They Live:

Geographic marine distribution of the Atlantic salmon in the North Atlantic Ocean. Courtesy of Eva Thorstad and Kari Sivertsen.

There are three groups of Atlantic salmon: North American, European, and Baltic. These groups are found in the waters of North America, Iceland, Greenland, Europe, and Russia. Atlantic salmon spawn in the coastal rivers of northeastern North America, Iceland, Europe, and northwestern Russia. After spawning, they migrate through various portions of the North Atlantic Ocean. European and North American populations of Atlantic salmon intermix while living in the ocean, where they share summer feeding grounds off Greenland. The North American group historically ranged from northern Quebec to Newfoundland and to Long Island Sound. This group includes Canadian populations and U.S. populations. In Canada, healthy populations still exist today, however, many populations are severely depleted.

The GOM DPS at listing included the nine remnant populations in central and eastern Maine. River specific populations still persist in the Sheepscot, Penobscot (including the Ducktrap), Narraguagus, Pleasant, Machias, East Machias, and Dennys rivers. GOM salmon leave Maine rivers in the spring and reach the seas off Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, by mid-summer. They spend their first winter at sea south of Greenland and their second growing season at sea off the coast of West Greenland and sometimes East Greenland. Maturing fish travel back to their native rivers in Maine to spawn after 1 to 3 years.

Lifespan & Reproduction:

Atlantic salmon have a complex life history and go through several stages that affect their behavior, appearance, and habitat needs. They are anadromous, which means that they are born in freshwater, migrate to the ocean as juveniles, and then return upriver to spawn as adults.

When spawning in the fall, the female salmon uses its tail to dig nests in the gravel where the eggs are deposited. These nests are called redds. Over winter, the eggs develop into very small salmon called alevin. In the spring, the alevin swim out of the redd and are then called fry. Fry grow into parr, which are only 2 inches long and are camouflaged to protect them from predators. For 2 to 3 years, the parr grow in freshwater before transforming into smolts in the early spring. The silvery smolts’ gills and organs change, allowing them to swim to the ocean where they spend 1 to 2 years maturing into adults.

The adult Atlantic salmon return to the river where they were born to lay eggs. After spawning in freshwater, the adults, now called kelts, swim back to the ocean to possibly return to spawn again in future years.

Females returning to spawn after two winters at sea lay an average of 7,500 eggs. Out of these eggs, only about 15 to 35 percent will survive to the fry stage.

Threats:

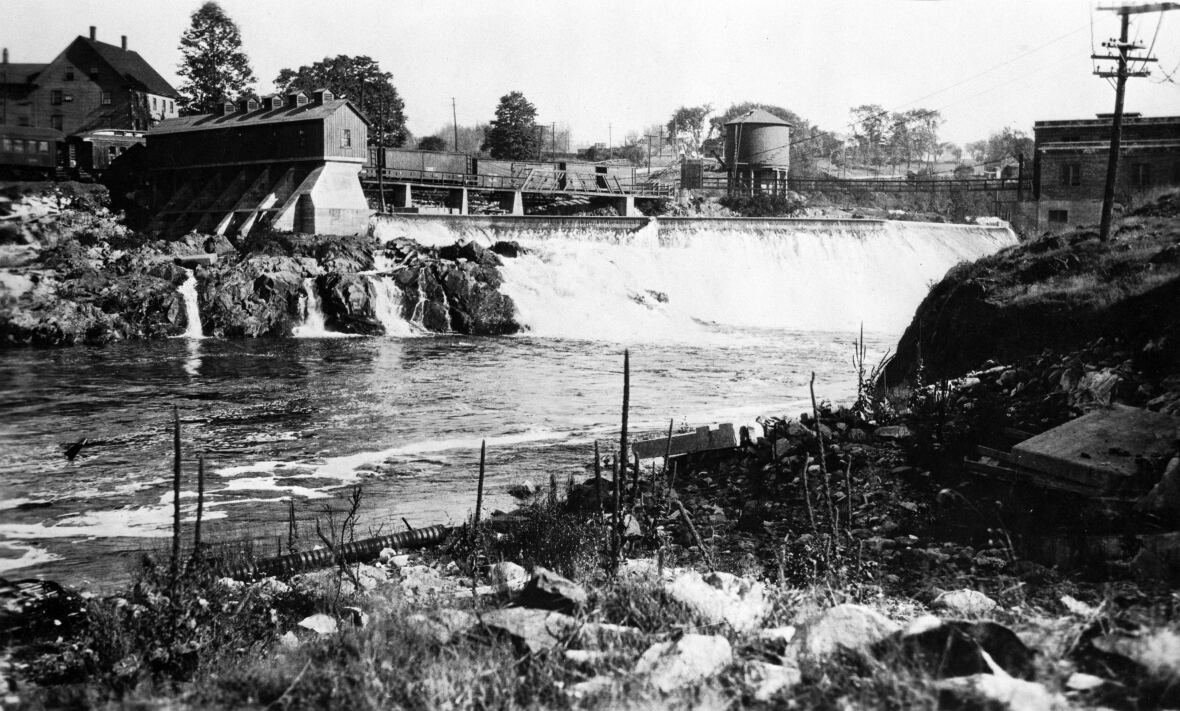

Canada fared no better than the US Northeast – milltown dams destroying bountiful salmon spawning runs. Above, the dam and power station on the St. Croix River can be seen from the town’s main street, Milltown Boulevard. They were originally built in 1881, to power a cotton mill. It’s one of the oldest hydroelectric plants in the world. Photo New Brunswick Archives.

Atlantic salmon populations are exposed to a variety of threats. The most significant threats to their survival include impediments—such as dams and culverts—that block their access to quality habitat, low freshwater productivity, ongoing fisheries off the shores of Greenland, and changing conditions at sea. Salmon also face many other threats that affect their survival, such as poor water quality, degraded freshwater habitats from land use practices, fish diseases, predation from introduced and invasive species, and interbreeding with escaped fish raised on farms for commercial aquaculture. All of these factors are compounded by climate change and Atlantic salmon are the most vulnerable finfish in this region to this overriding stressor.

Source:

Learn more about threats facing the endangered Gulf of Maine population of Atlantic salmon. Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 05/17/2022. Click here. . .