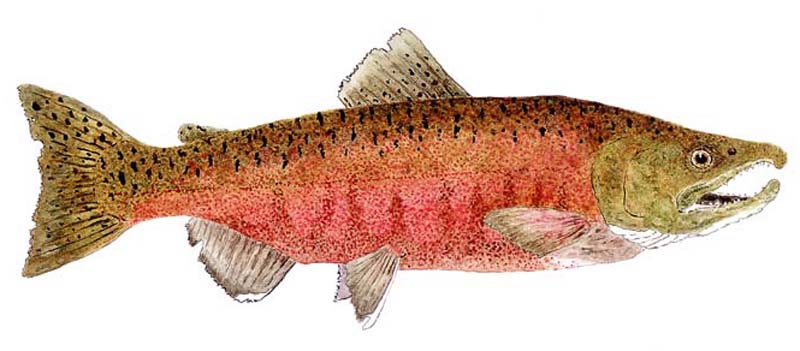

Chinook salmon – U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. IGFA World Record on a fly 71 lb. 8 oz. on 8-pound test – Rogue River, Oregon [October, 2002].

Coming Home to the Klamath

A genetic discovery may help restore chinook salmon to reopening river habitats.

The Klamath was once the third-largest salmon-producing river in the United States, and its fish are still prized by Indigenous tribes that live along its winding path. In the Klamath, as in many other rivers, chinook salmon come in two main types: spring-run and fall-run. Spring-run fish start their migration from the river’s estuary four to six months before their fall-run cousins, and their return spawning run takes them farther up the river. Over time, however, human activities including mining, agriculture, and dam construction all but swept spring-run fish from the upper Klamath. Today, only the fall run of chinook salmon is large enough to support fishing.

“We’re just accelerating things. Within 10 years, we could have thriving spring-run chinook salmon populations. After all, the dams have been up for 100 years.”

Male Chinook (King) Salmon in spawning colors. Art provided courtesy of Thom Glace.

People have long recognized spring- and fall-run patterns, but scientists couldn’t actually explain what caused this distinction. “We found these curious patterns again and again,” Garza says, “even though they were the same type of salmon.” Once they acquired the technology to quickly sequence fish DNA, however, the scientists started analyzing the genes of salmon that spawned at different times. “We found a single region in the genome that’s responsible for the difference between early- and late-migrating fish,” Garza says. This led them to wonder whether they could re-create the missing spring-run salmon by crossing fall-run salmon with those that have the early-migration gene.