Westerners think the steelhead/rainbow trout [Oncorhynchus mykiss] world belongs exclusively to them, but the rainbow was introduced into the Great Lakes in 1876 in Michigan’s Au Sable River (tributary to Lake Huron). From this, and subsequent introductions like mature “steelhead” about 50 or so years ago, that rainbow model quickly colonized throughout the Great Lakes with Eastern Ohio and Western Pennsylvania’s river systems becoming “hot spots.” The two volume “Wild Steelhead” can be reviewed here.

A look into the multi-million-dollar steelhead fishing industry in Ohio and Pennsylvania

Barbara Mudrak was a reporter for 25 years, mostly with the Akron Beacon Journal, and recently retired from teaching English and news writing at Alliance High School. She can be reached at editorial+barb@farmanddairy.com.

By Barbara Mudrak / Farm & Dairy / October 16, 2020 / Excerpt

NOTE: Excerpted . . . .

. . . Steelhead Alley

It’s no accident that the rivers, creeks and streams that drain into the south shore of Lake Erie from Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York are collectively called Steelhead Alley. Not only are anglers praying for rains that will start the steelhead runs, but business owners in those areas as well.

That’s particularly true in the northwest corner of Pennsylvania, which juts into the Lake Erie shore.

“Erie County in and of itself is the freshwater fishing capital of Pennsylvania,” said Karl Weixlmann, vice president of the Pennsylvania Steelhead Association.

With Presque Isle Bay and the many rivers and streams flowing into Lake Erie, the area provides “world class steelhead fishing from fall through spring.”

Weixlmann, who has been a fly fishing guide for 20 years and has authored three books on the subject, said steelhead fishing contributes “millions and millions of dollars” to the local economy.

It provides income not only for fishing guides, outdoor suppliers and charter boats, but for hotels, restaurants and other businesses as well. In a normal year, people travel to the area from all over the country, even other countries, to fish for steelhead.

Weixlmann has customers who make the trip from Denmark every year. “Unfortunately this year, we’re feeling the repercussions of COVID,” he said.

He and others are hoping that when steelhead runs begin, the regular crowd of anglers will follow. After all, “fishing is a great outdoor activity where you can social distance and still have a good time. And this year, it’s a great way to help local businesses,” he said. . . .

Steelhead anglers are hoping for a “rain event” that will lure their favorite fish upstream. Steelhead fishing is a multi-million-dollar industry in Ohio and Pennsylvania that supports not only fishing guides, outdoor suppliers and bait shops but hotels, restaurants and other businesses as well. (Ohio Division of Wildlife photo)

. . . Big business

Steelhead fishing is also a multi-million-dollar business in Ohio. Surveys by The Ohio State University School of Environment and Natural Resources and the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife showed “steelhead anglers reported significantly higher replacement costs for rods and reels, lures and tackle, and outdoor wear” than other anglers, spending more than $2,000 — 43%, of their total equipment costs — on steelhead alone.

Adding their cost of travel, steelhead anglers each contributed more than $800 to the Ohio economy that year, almost twice as much as “the average license holder.”

The survey concluded that “Ohio steelhead anglers fish more frequently, spend more money on fishing…are more motivated to fish (and) are more satisfied with their fishing experience” than those “average” anglers, making them “ an important stakeholder group” in the management of Ohio’s fisheries.

Stocked

Of course, Steelhead Alley only got its name because of the tremendous stocking efforts and management in its three home states.

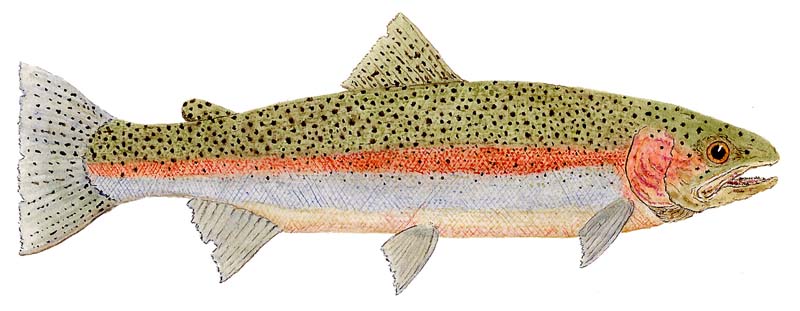

Steelhead are basically rainbow trout, which are native to rivers and streams of the Rocky Mountains and west. Except while rainbows spend their entire lives in freshwater, steelhead migrate to the Pacific Ocean to grow up, only coming back to the streams to spawn.

About 50 years ago, someone decided to import steelhead to the Great Lakes “just to see what they would do,” said Curtis Wagner, fisheries management supervisor for the Division of Wildlife District 3 office in Akron, which covers 19 counties in Northeast Ohio.

What they did was grow, really well. The lakes provide them with an abundance of insects, small fish and other food items. But when it came to reproducing, some had a problem, especially in the southern Great Lakes.

Steelhead require cold water for successful spawning, and tributaries in the south often get too warm — and too shallow — in the summer.

“It’s not that they can’t reproduce; some do,” Wagner said. But in the lower Great Lakes, especially Lake Erie, “they don’t reproduce successfully enough to sustain a sport fishery.”

The Lake Erie fishing regulations for Ohio had a limit of five steelhead (or salmon, or other kinds of trout) per person per day between May 15 and Aug. 31 of this year, and two fish per day between Sept. 1 and May 16 of next year, with a minimum size of 12 inches in both seasons.

Adult steelhead trout watercolor illustration by award winning artist Thom Glace.

Importing eggs

To get that sustainable fishery, the Division of Wildlife started getting eggs from wild steelhead that frequent the northern Great Lakes. In the past 25 years, the eggs have come almost exclusively from the Manistee River, which flows into Lake Michigan, though recently some have hailed from Wisconsin as well.

The eggs have developed enough so that the eye is visible, making them easier to transport safely. They’re all transported to the Division of Wildlife hatchery in Castalia, Wagner said.

Not coincidentally, Castalia is the site of the Blue Hole, but there are also other deep-water wells in the area with enough cold water to sustain the steelhead till they grow to yearlings, usually six to eight inches long. That’s when they’re released in the Vermilion, Rocky, Chagrin and Grand rivers, and Ashtabula and Conneaut creeks.

The division’s goal is to release 450,000 a year, which they usually meet or exceed.

Conneaut Creek

Conneaut Creek also gets steelhead stocked by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Most of the steelhead return to the streams where they were released, though some may become “strays” and go elsewhere, Wagner said.

Similarly, some of the steelhead released in Pennsylvania and New York migrate to Ohio tributaries to spawn. And unlike salmon, steelhead don’t just spawn and die; they can come back year after year.

I used to fish Walnut Creek [Walnut Creek is a 22.6-mile tributary of Lake Erie in Erie County, Pennsylvania] in sub zero weather of January and February. And other than my mates never saw anyone – ever, and that was for years. Photo by Keystone Anglers Guide Service.

Even as steelhead anglers wait for rain, they are having success fishing the shores, piers and breakwalls of Lake Erie, and the mouths of the tributaries. In November and December, the runs in the rivers should be at their peak.

And even if the rivers are frozen in January and February, fishing is still possible, Blotzer points out. After the ice breaks, river action will be “hot through the first week of May.”

Then, when the steelhead return to the lake, “you can still catch them when you’re trolling for walleye or perch,” he said. “Between the lake and the streams, you can catch them pretty much year round.” Which makes a lot of steelheaders happy, pretty much year round.

Read the complete story here . . .