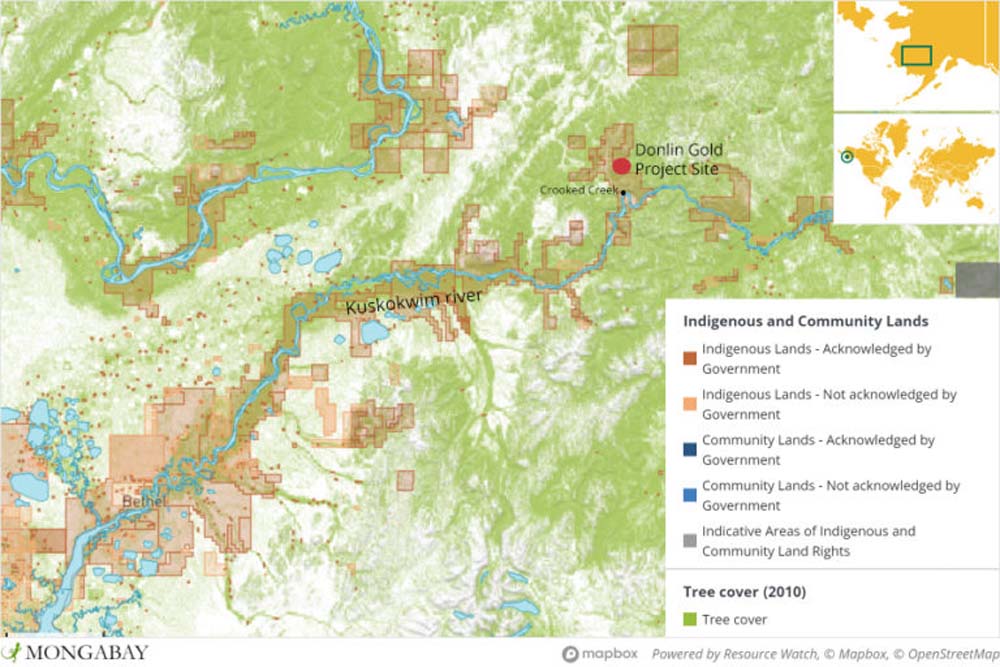

The mine site is located in the Crooked Creek drainage, 16 kilometers (10 miles) from an Indigenous community and the Kuskokwim River. It sits directly on several streams that feeds Crooked Creek. Image courtesy of Mongabay.

Alaskan Indigenous leaders fear impacts on salmon streams by mining project

- Mining company Donlin Gold is seeking to develop one of the world’s largest open-pit gold mines near Alaska’s Kuskokwim River, a spawning ground for several species of salmon, which make up 50 percent of local communities’ diet and subsistence lifestyle.

- According to Donlin Gold, Native corporations have already approved of the mine and the best available technology will be utilized to meet or exceed all air and water quality standards while providing employment opportunities.

- Tribal leaders argue Native corporations agreed without consulting tribal governments, who are shareholders, and fear mercury contamination and the disruption of their access to hunting and fishing grounds, as underlined in the project’s Environmental Impact Statement.

- Tribal councils have brought the matter to the Alaska Superior court and are appealing two certifications necessary for construction due to exceeded levels of mercury and impacts to salmon streams.

Laurel Sutherland began her journalism career in 2018. Prior to joining Mongabay, she worked for the Stabroek News, one of the leading print and digital news agencies in Guyana. She has provided news coverage on several beats at once, including on the environment, the extractive industry and Indigenous Peoples. She also has experience in data research, entrepreneurship, business management; and volunteered with the Pan Amazon Ecclesial Network.

For Indigenous tribes living in Alaska’s remote Yukon-Kuskokwim region, southwest of the state, the future is bleak and uncertain. Tribal councils worry that plans to construct a 6,474-hectare (15,990 acres) open-pit gold mine near the Kuskokwim River watershed will have grave impacts on salmon habitats, their traditional ways of life and their health.

“This development could possibly destroy our livelihood, rivers and sea mammals that we depend on,” said Fred Phillips, representative of the Indigenous Village of Kwigillingok tribal council. According to him, tribes are not willing to take the risk.

The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta (YKD) drainage is part of a rich biome encompassing coastal wetlands, tundra and mountains that supports the subsistence lifestyle of three distinct Alaskan Native groups; The Yup’ik, Cup’ik and Athabascan. To access the remote region, one needs to go by boat when the Kuskokwim River is flowing, or truck, snow machine and four-wheeler when the river is frozen.

Draining into the Bering Sea to the west, the Kuskokwim River, and many of its tributaries, are designated as Essential Fish Habitat (EFH), under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act for Pacific Salmon. This is a legislation that manages marine fisheries in US waters.

The sprawling river is a vital source of food for the 38 communities that reside alongside it, serving as a running ground for the chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) and sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). Given the remoteness of the region, the communities rely on subsistence fishing.

Salmon makes up more than 50 percent of the tribe’s annual diet.

The Kuskokwim River in southwestern Alaska. Image courtesy of Travis via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

A mining site near salmon habitats

All salmon species usually migrate from the oceans late spring or early summer, but spawn during different months during the two seasons. While no endangered or threatened fish species are found in the drainage, the chinook salmon are of special concern in recent years due to their low population. The Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) record limited numbers of sockeye and pink salmon in Crooked Creek, one of the many tributaries of the river. This includes 12 other species of fish, including the Dolly Varden trout (Salvelinus malma), Arctic grayling (Thymallus arcticus), pike fish (Esox lucius) and two species of whitefish.

So, when Canadian-based mining companies NovaGold and Barrick Gold, through subsidiary Donlin Gold, proposed a plan to construct a massive open-pit gold mine along a tributary of the Kuskokwim about a decade ago, most affected communities disagreed. In 2019, 35 of 37 tribal governments voted in disapproval.

They feared that negative construction and mining impacts on wildlife and environment cited in the EIS would lead to disrupted access to subsistence hunting and fishing, in addition to filing fragile wetlands.

There will also be a 40 percent increase in mercury deposition to surface waters near the mine, resulting in fears the mine may harm community members’ health.

Construction plans include the mine, a 220 MW power generation plant, a tailings dam, access roads, a water treatment plant, ports, an airstrip and a steel pipeline that would be constructed to transport natural gas to the mine site. Donlin is currently conducting exploration activities.

With a mine life of 27 years, the mine is estimated to produce nearly 37 million grams (1.3 million ounces) of gold per year, making it one of the largest open pit gold mines in the world.

The mine site is located in the Crooked Creek drainage, 16 kilometers (10 miles) from an Indigenous community and the Kuskokwim River. It sits directly on several streams that feeds Crooked Creek.

The EIS states that approximately 7.5 kilometers (4.7 miles) of stream supporting fish and 9 kilometers (5.6 miles) of stream not supporting fish habitat would be lost when construction of the road and pipeline begins. The mine will contribute to increased greenhouse emissions. The exact estimate was not stated in the EIS.

An Administrative Law Judge found that the water quality standards for mercury will undeniably be exceeded by the project in numerous locations. Alaska’s superior court is currently allowing the ADEC time to review additional scientific information.