The mouth of the Elwha River. Photo credit Northwest Travel & Life.

Until recently, the Elwha River’s nearshore was an ankle-twisting pile of cantaloupe-size rocks, with occasional swampy pools and thin bunches of sea grass. Now, with the river free to push millions of tons of sand, soil, and woody debris downstream, it has grown by some eighty-five acres

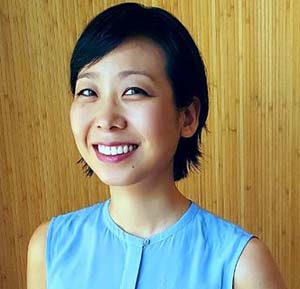

Story by E. Tammy Kim / New Yorker Magazine

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ne morning in late August, at the peak of an unusually hot summer, I joined a group of scientists on the northern coast of Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula to perform a fish census. We trudged over a dike to a pristine beach just west of the mouth of the Elwha River. Chris Byrnes, a state biologist, and Sheri Washington, an intern with the nonprofit Coastal Watershed Institute (C.W.I.), rowed a small skiff into a shallow pond. Byrnes manned the oars while Washington let out the seine, a net embroidered with buoys along its top edge and lead weights along its bottom, which unfurled into the water like layers of meringue. Once the seine was in place, forming an underwater screen, four of us waded in bellybutton-deep, grabbed hold of its ends, and dragged it toward the shore. (At this point, another intern discovered a pinhole leak in her waders, “somewhere north of the crotch.”)

Near the edge of the pond, still half-submerged, we crowded around the seine and used our fingers to comb the catch. Byrnes grabbed a little fish with a spotted fin and dropped it into a clear, ruler-lined box of water. “Oncorhynchus mykiss,” he said. “Steelhead, seventy, no clip, no tag.” (Translation: seventy millimetres in length, no hatchery marking.) He let it swim away and resumed the inventory. From dry land, Anne Shaffer, the C.W.I.’s executive director, took notes as Byrnes continued to holler. Some of the fish he measured twice—once from snout to tail end, and once from snout to tail fork. “Ten sticklebacks under thirty!” “Coho, one-thirty, one-eighteen, no mark, no tag!” “Chinook, one-sixteen, one-oh-two, no clip, no blip!” (This was a particularly good find, since the leopard-spotted Chinook salmon is classified as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.) A few other reports went unrecorded. “We’ve got tons of snails,” Washington said, ten minutes into the census. Later, a biologist named Tara McBride said, “The fish won’t stay still enough to be measured, little fucker!”

Adult Chinook salmon hit the end of the river in a pool below the Elwha Dam that used to block their upstream spawn. See featured image NOTE for credit and link.

Shaffer and her colleagues have sampled the Elwha’s nearshore region, where the river meets the ocean, once or twice a month since 2006. August, of course, is an ideal time; when you go in January, McBride said, “your fingers freeze, so you just put ’em under your armpits.” The work of the C.W.I. now seems particularly vital, because, for the first time in several generations, the forty-five-mile-long Elwha is a living river, end to end. Between 2011 and 2014, two large, century-old hydroelectric dams were demolished as part of a federal recovery effort. Spurred by decades of litigation, the Elwha restoration is the largest dam-removal and river rehabilitation project in U.S. history. The smaller of the dams was illegal from the start, built in violation of the treaty rights of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and a state law mandating passage for anadromous fish—species, like salmon and steelhead trout, that return from the ocean and migrate upstream to spawn. Their life cycle is sacred to the tribe and difficult not to anthropomorphize. Hatched in freshwater streams, the salmon swim dozens of miles toward the sea, where they spend their adulthood. Then, when nature calls, they swim all the way back, their skin, accustomed to saltwater, peeling away as they search for their pebbly natal streams. There they mate and die, giving life to bears, birds, and trees.

Until recently, the Elwha’s nearshore was an ankle-twisting pile of cantaloupe-size rocks, with occasional swampy pools and thin bunches of sea grass. Now, with the river free to push millions of tons of sand, soil, and woody debris downstream, it has grown by some eighty-five acres. Shaffer has spotted a range of new species in the estuary’s ponds, such as bull trout, redside shiner, and slender eulachon. There are new human visitors, too. “The changes to the beach have changed the way the community interacts,” LaTrisha Suggs, the assistant director of river restoration for the Elwha Tribe, told me. “Back when there were just cobbles, you only had hearty people out there, but now you have people going out to the beach every weekend.”

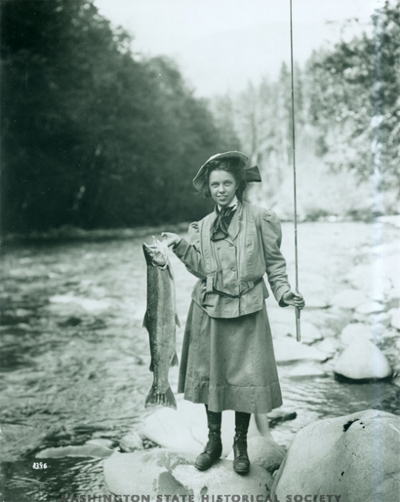

This kind of image is expected in the near future . . . Eleanor Chittenden, daughter of Brigadier General Hiram Chittenden, holds a steelhead trout on the Elwha River during an outing of the “Mountaineers.” Taken August 1, 1907, by Curtis Asahel. Photo provided courtesy of the Washington State Historical Society.

The change is most visible at Beach Lake, a twenty-six-acre property that borders the Elwha reservation. For years, the dams starved the area of sediment, so homeowners armored the shoreline with concrete, riprap, and rows of boulders to prevent erosion. The C.W.I. recently purchased the land from a private owner, and in August removed some three thousand cubic yards of rock. Shaffer’s team expected modest resedimentation, but the transformation was far more rapid and dramatic than they’d thought possible. Within a few days, the beach had widened by many feet and was edged by soft, fine-grain sand. After several weeks, there were signs of species returning to the brackish waters—sand lance (a tiny prey fish), crabs, flounder, and squid. Once the restoration of the Beach Lake property is complete, it will be deeded to the tribe and opened to the public.

It’s a rare happy story in an age of environmental calamity. But, even with the Elwha dams out of the way, threats of every variety confront the Olympic Peninsula. Shaffer rattled off the ones that worried her most—fish from commercial hatcheries crowding out their wild cousins, the breeding of non-native Atlantic salmon in migratory streams, huge oyster and geoduck farms occupying precious shoreline, and, as on Beach Lake, barriers erected by city planners and wealthy homeowners. (And now, perhaps, President-elect Donald Trump’s nomination of the Montana congressman Ryan Zinke, an advocate of logging and drilling on federal lands, to lead the Department of the Interior.) Cleaning up a river, Shaffer observed, means accounting for factors far afield of its immediate path. It doesn’t help that the nearshore is miles away from the former dams and outside the confines of the park, giving it a somewhat marginal status. The river mouth and surrounding delta were excluded from the congressional budget for dam removal and river restoration; thus, the C.W.I. and the Elwha Tribe have relied on a patchwork of research grants to fund their decade-long studies of the area. . .

Story by E. Tammy Kim, member of The New Yorker’s editorial staff and the co-editor of “Punk Ethnography: Artists & Scholars Listen to Sublime Frequencies.”

Read something that means something. Get The New Yorker . . .

NOTE: Featured Image is of the lower Elwha River – resurgence. Tear down the dams and they will come. Photo credit The Seattle Times (Roaring back to life).