As the West suffers another summer of drought and fire, fishing holes there and elsewhere are feeling the heat

Christopher Solomon: Contributing Editor, Freelance Writer, Outside, The New York Times, Outside, The New York Times, Bloomberg News, Terra, The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Color Research & Application, National Geographic, Springer, Seattle Times, Yahoo Lifestyle, GQ and more.

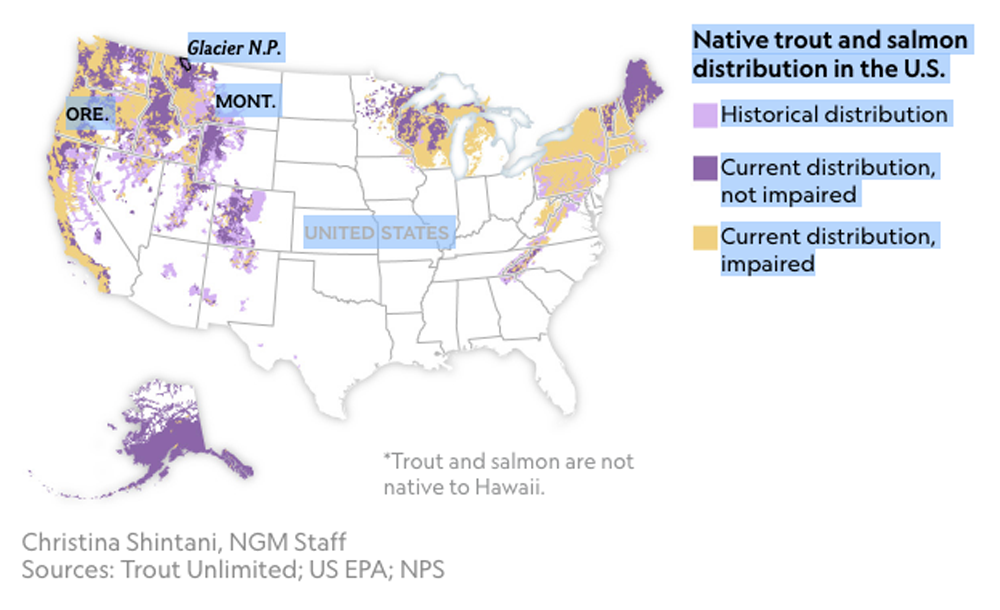

Climate change is shrinking the habitat of native trout and salmon. It warms the water in streams and lakes, intensifies drought in the West, reduces mountain snowpack—in general, it deprives freshwater fish of the continuously flowing, clean, cold water that many depend on.

Some non-native fishes, including brown trout and rainbow trout, thrive in warmer waters and compete for resources, hybridizing with native fish and exacerbating their struggle for survival. The Environmental Protection Agency identifies streams that are impaired by warmer water or pollutants.

. . .

Around the world, more people fish for fun than fish for a living—perhaps 700 million people worldwide, by one estimate. Americans are particularly passionate: More than one in seven of us grabbed a fishing rod in 2017. Most headed to freshwater—the nation’s lakes, rivers, and streams. Fishing inland waters for recreation props up the economies of entire small towns like Ennis, Montana and Maupin, Oregon, generating about $30 billion in direct spending alone in the U.S. each year.

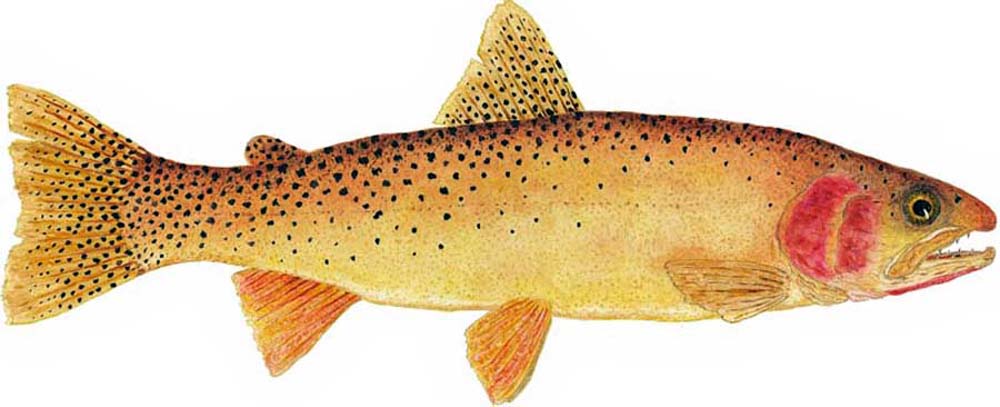

Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout by Thom Glace.

In the mountain valley where I live out West, I like to head to the water in the blue morning when the air still holds the beginning-of-the-world smell of river mud and rot. The river flows through bottomland flecked with cattle and cabins and ponderosa pine and, in the spring, bouquets of yellow balsamroot. Its waters hold some remarkable fish, like the world-weary Chinook salmon that each August will brush past a wader’s legs, intent only on sex and death. I am not so foolish to think that I own any piece of this Earth in any lasting sense, but more than anyplace, I think of this river as my own. I string the rod, guess at a fly to tie on, and dip both hands in the cold water like an ablution—a vestige, perhaps, of a Catholic upbringing. Then I get to work. To fish is to enter into a relationship with the world—to note each wrinkle on the water, and the insects that lie beneath the rocks, and a heron unfolding origami wings to head downriver. To fish is to pay attention. And to pay attention, deeply and unmixed by distraction, Simone Weil wrote, is itself a kind of prayer.