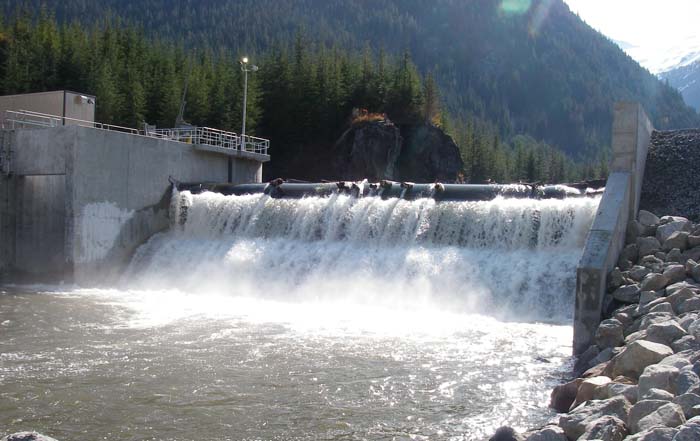

Put a dam in and fish migration and fish populations are crushed and the dynamics of an entire river is dramatically altered. Pictured, Toba Montrose Run of River Power Plant Intake – Alterra Power Corp. a subsidiary of Innergex Renewable Energy Inc., Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

By Jennifer Horton / System 1 Company / November 2008

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he rivers and streams of the Pacific Northwest used to be so full of wild salmon that fishermen liked to say they could cross the waterways on the fish’s backs. If salmon were the only means of crossing the rivers, those fishermen would be out of luck today. In California, Washington, Oregon and Idaho, salmon are extinct in nearly 40 percent of the rivers they were known to inhabit — at least 106 major stocks gone forever [source: Northwest Power & Conservation Council].

Around the world, the story is much the same: Global Atlantic salmon catches fell 80 percent from 1970 to 2000. In the United Kingdom, one-third of the salmon population is endangered according to the WWF, and in California and Oregon, the Pacific Fishery Management Council recently announced the strictest salmon fishing quotas in the region’s history due to the animal’s rapid decline [source: Young, Environment News Service]

The downward spiral of the salmon population is troubling for several reasons. This fish is far more than just a tasty source of omega-3s. Salmon are what’s known as a keystone species — like the engine in your car, their physical presence compared to the whole is rather small, but their importance to its functioning is vital.

Male sockeye, a Pacific salmon in spawning colors by watercolor artist/illustrator Thom Glace.

Not only are the fish a main source of sustenance for a variety of predators (more than 137 species), but their decomposing carcasses are a significant source of nutrients and fertilizer for trees [source: Hunt]. When the salmon go, the surrounding ecosystem likely won’t be far behind.

Unfortunately, there isn’t an easy solution for reversing the decline in salmon populations — everything from overfishing to El Nino and climate change have been linked to salmon depletion. The fish’s complicated life cycle — salmon begin life in a stream, migrate to sea for their adult life and finally return to their birthplace in order to reproduce — makes it even harder to pinpoint the primary factors leading to each population’s fall.

But researchers do know enough about the leading causes to label them with a nifty slogan. Keep reading to find out what the four Hs — harvest, hatchery, habitat and hydropower — are all about.