Mudding bonefish and a lone Albula vulpes. Casting for these pescados almost always involves dealing with the wind. Illustration by Robert W. Hines, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – A commons image.

Learn to take the wind out of casting

By Skip Clement

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]ost anglers of the fly with a lot of miles on their fishing odometer admit that their addiction to water and fish has on occasions gotten them mugged by a wrongly directed fly that finds an ear, back, butt, leg, friend, or his or her head.

I had convinced myself that one more false cast would enable reaching “tailing” brown trouts the size of settees. I was in New Zealand on a river that stopped trout at a falls of no more than 5- or 6-feet high. The base of the natural falls, a place too far for the wind that day, boiled with rolling backs and fins of trout – brown trout. It looked like a fall blitz in Montauk, New York.

I had no idea what was causing the boil and my guide, none other than New Zealand’s most famous guide (fly angling tournament champion, fly fisherman extraordinaire, world renown fly tyer, and author), Hughie McDowell didn’t either. There was nothing close to a hatch happening.

One punch knockout

The outcome in that New Zealand scenario was the last cast being short of the target by about 80-feet because the outbound fly never made it – I was at 70-feet. It punched me in the back-of-the-head – stopping us both in our tracks. An errant muddler fly traveling at Mach 1 speed (a well-hauled cast moves at + 200 mph) penetrated my skull, drew blood and left a welt the size of a poker chip.

The route your hand travels during the cast either makes you a good caster or a lousy one

At one time for all of us, the wind was a bad omen, a deterrent to good fishing, but as it turns out there are benefits from it, and simple casting alterations make it all happen in our favor, as well as muddling the view from down under.

However, it’s impossible to describe what to do for every single click of increased wind speed, or degree of angle it comes at you. You ultimately have to figure all that out on your own, but what you don’t need to do is to figure out how to make umpteen new “techy” casts.

There are only four directions that wind can attack your casting. Headwind, tailwind, wind at your casting arm side, and wind blowing into your offhand side.

Up to a point, you can double haul in any wind

The attached YouTube titled “Tim Rajeff on Handling Windy Casting Conditions,” Tim eludes to Joe Mahler’s headwind casting technique, but for clarity I add here what Joe has to say and his illustration demonstrates.

It’s possibly the best way to cast with or without a headwind.

Joe’s method of dealing with a headwind:

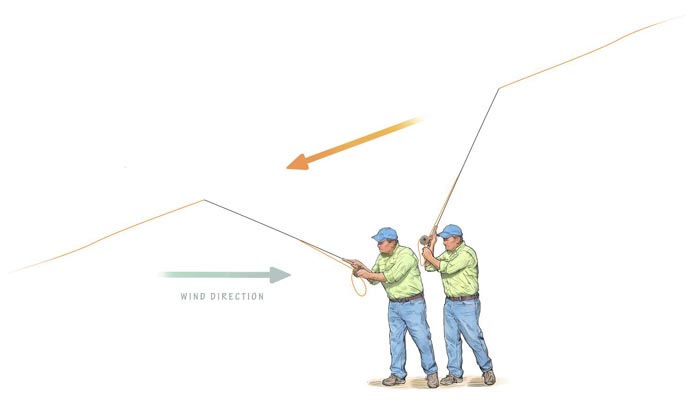

The headwind (or wind in your face) is the most dreaded of all wind directions, but many of my friends and students are surprised to find that this is the wind direction I usually prefer. If your casting accuracy is good, chances are that the same skills that you use for nailing your target also help you conquer a stiff headwind. The overhead cast is my choice for this kind of driving accuracy. I use the wind direction to quickly add energy to my backcast which gives me more time (a longer pause) to keep the backcast in the air, much like a kite.

To make the headwind overhead cast, start the pickup especially low, and stop the rod in a vertical position, sending the backcast in an upward trajectory. Allow the line to fully unroll and then drive it slightly downward with a solid stop.

Illustration provided by Joe Mahler.

If you’re an accurate caster, you probably also have the skills to deal with a headwind. Change the angle of your cast so your backcast unrolls in an upward trajectory, and drive your forward cast straight toward the target at a slight downward angle.

Some people drop the rod and use a sidearm cast in a headwind, and while that tactic does help to keep the line lower and possibly out of the wind, it also requires that you cast faster, as your line is closer to the surface. This isn’t usually a problem if you are standing on the deck of a flats boat, but it can be if you’re standing waist-deep in the river or sitting in a kayak. With either technique, shoot more line on your backcast and less (if at all) on the forward cast.” — Joe Mahler

If you cannot Belgian, you can’t play outside on windy days

The Belgian Cast, primarily thought of as a saltwater venue-cast and more specifically a flats/bonefish cast is a great open water-windy day cast no matter where you are fishing, and done right there’s no shortage of distance – the original purpose.

Who came up with that cast?

An Austrian riverkeeper named Hans Gebetsroither invented the “Oval” cast in the 1930s. In Europe, the Gebetsroither casting style was called Ovales Fliegengieben. Odd, that such a catchy sounding name didn’t get picked up on by outdoor pundits of the day?

The name “Belgium Cast” snuck into fly fishing nomenclature via the famous editor of Field and Stream Magazine, A. J. McLane in the early 1950s. The cast was brought across the pond by world casting champion, Albert Godart, a Belgian. He introduced it at a round of U. S. sponsored casting tournaments.

It wasn’t exactly a new technique to the Yanks. Lee Wulff had been preaching his “Oval Cast” for some time, but it never caught on

It’s easy to adopt, extremely useful in the wind – a must. It’s a popular solution with several Bahamian guides and known in the Caribbean among some of those guides.

The Belgian is also the answer to casting big, heavy, and bushy flies.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, a video is worth ten thousand pictures. Here’s two very good YouTube videos about casting in the wind and four other good casting in the wind video links:

Tim Rajeff/Echo Fly Rods

Shawn Leadon/Andros Island Bonefish Club – Belgian Cast: