Almost 300 miles of red canyon walls guard the mighty Colorado River and its rich collection of trouts. Image by Lees Ferry Anglers.

In a desert, I learned to fly fish

Dams, invasive species and roadways. All this, so I could go fishing

NOTE: With permission, we are republishing Maya L. Kapoor’s article from High Country News, June 21, 2018, in its entirety.

Maya serves as associate editor for our southern coverage area from Davis, California. She also writes about science, environmental policy and social justice. She has more than a decade’s experience as a field biologist and environmental educator in the Western United States and Latin America. HCN photo.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]fter a lifetime of recreational pacifism, I hooked my first catch. Kneeling on the sandy gravel beside the lake, I pinned the fish to the ground with my left hand and gripped a slender knife in my right. Then, I paused. I knew, in theory, how to cut off the head of a fish. But when I actually held a fish in my hands, I hesitated, a cold wind raising goosebumps on my arms. I huddled over the motionless trout with my back to the sun. I had no idea what I was doing.

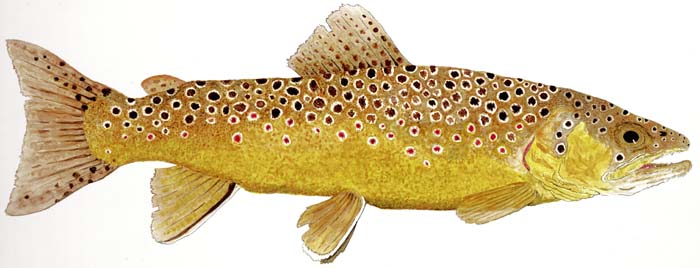

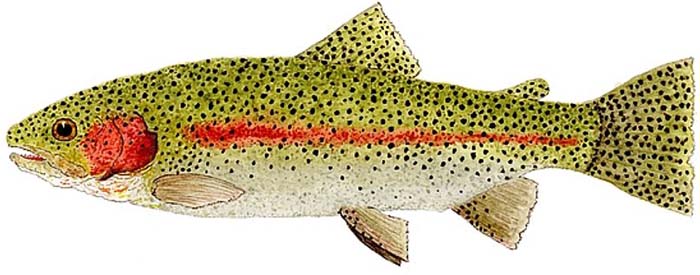

I had no idea what anyone else there was doing, either. Arizonans, I’d recently learned, love fishing. Arizonans love fishing to the point of damming creeks, moving earth, building lakes, and trucking fish in, just to catch them. In 2001, while the U.S. economy sank, people in Arizona spent more than $800 million on fishing-related costs, from rods and reels to lodging and fuel. Native Arizona trout species face extinction, thanks in part, to the competition, inbreeding and predation of the browns and rainbows introduced for sport. But no matter: Brown and rainbow trout flourish in Arizona’s built water systems, including reservoirs, urban lakes and streams. Brown trout were originally a European species; rainbows evolved in rivers on the West Coast of North America, near the Pacific Ocean.

The more I tried to understand fishing in Arizona, the less sense it made to me. I preferred waterways undammed, species locally unique. Then, a few years ago, I spent a weekend in a cabin near Rose Canyon Lake with three other anglers. At the water’s edge, I tried out bobber fishing — the kind you do on a sleepy Sunday, not exactly A River Runs Through It material — to see if I could make sense of the practice of this sport in such an arid place.

It was February, and Rose Canyon Lake, in the, was peaceful. Young ponderosas and manzanitas leaned in from the edges of the canyon, jays calling from their branches; cattails fringed the water, their white fluff floating in the breeze. Patches of snow lingered in the shade, and sheets of ice covered the shallows, even as sunlit ripples sparkled across the lake.

The Apache trout, Oncorhynchus apache, is a species of freshwater fish in the salmon family of order Salmoniformes. It is one of the Pacific trouts. It is also a threatened species. Photo by Joe DiSilvestro/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters – a commons image.

During the high season, May to October, anglers crowd the water’s edge for a fishing spot, but that morning I counted only three other groups. Four men in Army fatigues heckled each other on a dock across the lake. Once in a while their voices carried, as they teased one another about the size of their catches (“That’s not a fish! I don’t know what that is!”) and the relative hopelessness of their fishing techniques. To my left were two peaceable old men in dirty leather cowboy hats. “You never take more than your catch allowance, right?” they drawled at us. “That wouldn’t be right.” On our right, too far away to hear, three young Latino fathers and their little boys fished, occasionally shooting a BB gun at the sky. When nothing bit, the children giggled and chased each other into patches of sun, keeping warm.

The fish I’d caught gleamed in the morning light. The most natural motion seemed to be sawing a line under its pectoral fins, like slicing a loaf of bread. “Do it fast,” said Jess, a short, fit woman with blond hair who was a native fish researcher at the University of Arizona and my teacher for the weekend. “Don’t saw!” A quick decapitation was a humane decapitation. In theory, the fish was dead already, but there was a small chance that snapping its back hadn’t kill it. Lacking a trout-sized guillotine, I held my breath, pressing the blade into the trout’s flesh.

Mixed conifer forest dominated by Pinus engelmannii, Rose Canyon Lake, Santa Catalina Mountains, Pima County, Arizona. Photo by Bryan Davidson/Flickr – a commons image.

Brown trout always sounded to me like the name of a muddy animal consigned to silted ponds, something named in opposition to its prettier, more popular, rainbow sister. But my brown trout was beautiful, with leopardine spots on skin that shone silver in the sun, flashes of crimson under its gills. The trout was surprisingly soft under my cold palm, its skin like silk against my own. I had expected it to feel dead — rough, cold, stiff, like something that came out of the grocer’s freezer. Instead, under my hand, I felt taut skin binding lithe muscle into form. I didn’t want to admit this to Jess or the others in my group, but I was enchanted by the fish. My fish was a survivor, too, at least until I hooked it: According to the Arizona Game and Fish Department, brown trout released in Rose Canyon Lake took several years to grow to its size.

My fish was part of Arizona’s giant angler economy. In better weather, wildlife managers dropped fish into Rose Canyon Lake about once a month, and just as quickly, anglers pulled them out again. The trout before me, motionless on the shoreline, existed for what is called put-and-take fishing. On a published schedule, hundreds of 11-inchers were thrown into the lake, along with the occasional “incentive” fish — giants bred at the state hatcheries. With my $63 non-resident fishing permit, I had become a part of that economy. I wondered what else I was part of now. If these fish were grown indoors and stocked outside for me to catch, was this an escape from, or an extension of, my urbanized life?

The brown trout, Salmo trutta, imported from Europe in the 1800s flourished in North American environments. In many instances outbred and out fed its native cohabitors which diminished native fish stocks to the point where extinction occurred or became possible. Illustration provided by Thom Glace.

I sat back on my heels, wiped the bloody knife clean on my jeans, and grinned at the fish head gazing up at me from the ground. Jess, who had lent me her knife, was not impressed. “You’ve got to be careful closing your eyes,” she said. “Sometimes the body jumps. You could cut your hand.” I did not tell Jess that the first time I tried to open a can of sardines, I ended up getting stitches. Instead, I proudly studied my bloody handiwork. Where there had been one whole fish, two pieces now lay in the dirt. I was now a participant in a quintessential American pastime, the catching and eating of a meal. This wasn’t just so I could text my siblings pictures of fish guts while they were at work (though I did); I wanted to have the full fishing experience — to take responsibility for my catch by turning it into dinner. How else would I understand the culture of fishing, where this kind of thing was normal? Plus, to be honest, my diet was mostly vegetarian, and I really just wanted to eat some fish.

One of my neighbors, a middle school science teacher in his 40s, did not understand why I had never been fishing before. He told me his grandfather had taken him when he was a kid. I explained that my grandfather had been a vegetarian

“What are you,” he asked, “Pentecostal or something?” His question confused me. Were Pentecostals vegetarian? I had a vague idea they did something with snakes.

“We’re Hindu,” I said. Later, other friends assured me that vegetarianism was not a Pentecostal tradition. It was a Hindu one, though. My family was extremely open-minded about personal interpretations of our traditions (my parents loved a good steak), but I had been vegetarian on and off for 21 years at the time of my fishing trip. I was willing to relax my food rules, though, if it would bring me closer to understanding why we had a recreational fishing industry in the desert.

“Put the knife in here,” Jess said, indicating the orifice through which the fish, until recently, conducted its reproductive business. “Then hold the knife at an angle and cut up.” I held the fish on its side and slid the knife into the flesh, then pushed it away from my abdomen and through the sternum. The fish fell open like a book; together, Jess and I read the chapters of its life. “It’s female,” Jess said, digging the fish’s ovaries out from where they lay underneath the digestive system. “Look — full of eggs.” Jess handed me a translucent orange sac, long and skinny like a tiny hot dog, crammed with little shining beads. “She’s early to be this fertile. It’s only February.” She was ready to breed when she swallowed the hook.

“Here’s her liver, I don’t know what it’s doing up here,” Jess continued, indicating a dark, smooth organ. I held the glistening liver in my fingers. The stomach was a rubbery white tube shaped like a flower on one end. The swim bladder, deflated, barely showed against the fish’s back.

Rainbow trout, Onchorhyncus mykiss, are probably the most common species of trout in North America. They are native to the Pacific coast states, western Canada, Alaska, and Kamchatka peninsular in Russia. They too, like the brown trout, outbreed and predatorily vanquish other trouts, like the Arizona Apache trout. Rainbow trout illustration provided courtesy of Thom Glace.

After I’d removed everything, I ran the back of my thumb nail up the fish’s spine, bottom to top, the way I had seen Jess do with other fish, scraping out the last of the congealed blood. There. My fish was clean — minus the dirt, gravel and dead grass pasted all over it.

It would have been easy for me to discount my trout, to look around and reject the whole situation. Environmental economists talk about existence value, how something can matter to people even if they never get to see it. Polar bears had existence value to me. So did whales. On a local level, so did native biodiversity. Native desert trout, formed by our capricious waterways, impressed me with their strength of body, their endurance. Whether or not I ever saw a Gila trout or an Apache trout — Arizona’s state fish — in the wild, I wanted to know they were out there, streaking through clear water, stalking caddis flies, leaning into currents. Other Arizonans agreed: Our endangered species management was funded by a voter-approved measure that apportioned some of the state’s lottery tax for conservation.

I asked Jess if the remnant of the natural creek feeding Rose Canyon Lake harbored native fish species. Her answer was no; the lake was artificial, and prior to its construction, no trout swam on Mount Lemmon. Here, in high mountains looming above the Sonoran Desert, we built a lake and put in fish. We put in roads, walkways, docks; added crayfish; built houses; shot some animals; raised and released others. All this, so I could go fishing. There may not have been native fish swimming around the creek burbling nearby as I sat flicking entrails into cattails, but their ghosts nibbled at the edges of my conscience. If the point of managing Arizona’s water systems was to protect native biodiversity and natural systems, then Rose Canyon Lake was a spectacular failure.

But if the point was getting people out of the city and into the forest, Rose Canyon Lake was a success. Across the West, the story was more complex than recreational fisheries competing with native trout fisheries. All of the region’s trout species, whether introduced or native, depend to some extent on human husbandry. Like rainbows and browns, native trout live in water left over from thirsty crops and cities. Native trout, too, come from fisheries, where managers struggle to keep the fish’s behavior wild, their genetics diverse. Native trout take rides by mule, backpack, even helicopter, to be stocked in their historic ranges, then rescued from fires. Perhaps this is the truly quintessential American pastime: managing all of our outdoor landscapes, deciding what lives where, and why.

A better way to cover a lot of miles of trout waters. Image Lees Ferry Anglers.

Jess instructed me to wash off my fish. I held the trout in my palms and dipped her gently in the lake. The frigid water made my hands ache; cursing earnestly, I swished the fish, then tossed her onto the frozen shallows to keep cool. I rubbed my benumbed fingertips and looked around for something non-fishy to eat. To catch one fish and kill it wasn’t the point of learning to fish. I was genuinely trying to adopt a hobby, at least for a day. So after a snack, I baited my hook with a new smorgasbord of fish treats — fake maggots, salmon eggs, something that looked like orange play-dough.

“Aim for right next to that big log,” Jess said. “If I were a trout, that’s where I would live.”

I decided that if I did catch another fish — which seemed unlikely, given that I felt guilty even looking at the live earthworms Jess brought, and that I wasn’t having any luck with any of her fluorescent artificial baits, not even the sparkly pink one or the fake salmon eggs laced with something called “SEXattract” — I would release it. I wondered if I could release, too, all of the contradictions swirling inside me. To the part of me that enjoyed the adventure, release meant finding a way to live in the landscape, not just near it. But perhaps I also needed to release my idea of untrammeled nature. Managed landscapes and wild landscapes are strung by a taut line. Increasingly, as Arizona’s population grows and its climate becomes hotter and drier, Arizonans will choose what swims in our water, and even where that water flows.

I carried my rod to a flat spot on the water’s edge, looked around to make sure no other humans were close enough for me to hook, and snapped out a cast that smacked the water right in front of me. Swearing luridly — I seem to have gotten that part of fishing down — I turned my reel, bringing in the hook so I could try again.