The name “sockeye” is a corruption of an Indian tribes’ word “sukkai.” They average of 8-pounds and grow to 3-feet long. While spawning, the sockeye salmon is bright red with a greenish head. Later in their lives in the ocean, they turn to a silver with some blue and black on the head. Colors of the sockeye are very dependant on what stage of its life it is in. Life span is about five years. Sockeyes usually spend about one or two years in freshwater before migrating into the ocean. Adults usually stay in the ocean for 2 years and then go back to the freshwater to spawn. Wikipedia commons [Google Sites] image.

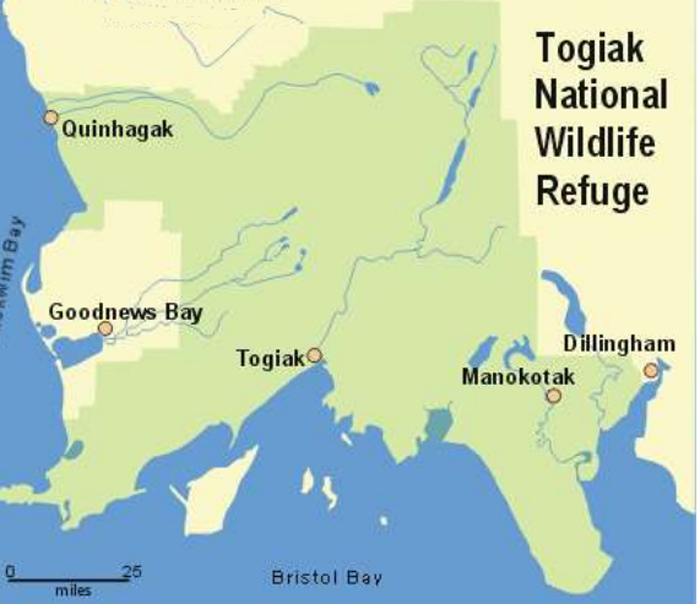

Alaska’s Togiak National Wildlife Refuge is in the current administration’s kill zone, and the divvying up of our public lands is happening now in DC’s back rooms – on our watch

By Skip Clement with illustrations by Thom Glace

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ooner than most think the current in-power thinkers with continued conservation disregards will ravage one of our most valuable biospheres, the primordial landscape of Togiak National Wildlife Refuge, with a system of highways, oil & gas wells, logging camps, extraction mining, and sooner than later keep-out signs.

What are the wonders and uniqueness of Togiak National Wildlife Refuge we need to protect?

The refuge is dominated by the Ahklun Mountains in the north and the cold waters of Bristol Bay to the south. The natural forces that have shaped this land range from the violent and powerful to the geologically patient. Earthquakes and volcanoes filled the former role of extreme forces, and the marks left by those event can still be found. Paradoxically, it was the gradual advance and retreat of glacial ice that carved many of the physical features of this refuge.

The refuge has a surface area of 4,102,537 acres. It is the fourth-largest National Wildlife Refuge in the United States as well as the state of Alaska, which has all eleven of the largest NWRs. It is bordered in the southeast by Wood-Tikchik State Park, the largest state park in the United States.

Alaska’s Togiak National Wildlife Refuge. Topographic maps of Togiak National Wildlife Refuge may be purchased from many retailers, or online through the U.S. Geological Survey’s website.

Wildlife in a kaleidoscope of landscapes

The refuge is home to 48 mammal species, 31 of which are terrestrial and 17 marine. More than 150,000 caribou from two herds, the Nushagak Peninsula and the Mulchatna, make use of refuge lands. Wolf packs, moose, brown and black bear, coyote, Canadian lynx, Arctic fox, muskrat, wolverine, red fox, marmot, beaver, marten, two species of otter, and porcupine, and other land mammals are found throughout the refuge. Seals, sea lions, walrus, and whales are located at various times of year along the refuge’s 600 miles of coastline.

Within the refuge, the waters produce over 3 million Chinook, sockeye, coho, pink, and chum salmon. Not including the five species of salmon that inhabit the region, there are 27 species found in the waters, including Dolly Varden, Arctic grayling, and rainbow trout. The region’s salmon is a primary subsistence source for locals and provide a significant commercial and recreational fishery.

Northern pike – Illustration by Thom Glace.

Arctic char – Illustration by Thom Glace.

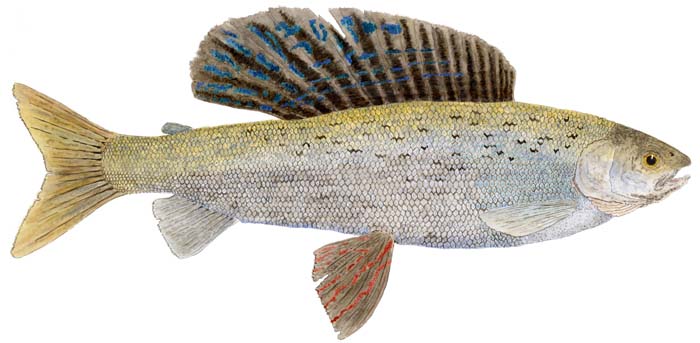

Grayling – Illustration by Thom Glace.

Male Dolly Varden by Award winning watercolorist Thom Glace.

Lake trout – Illustration by Thom Glace.

Some 201 species of birds have been sighted on Togiak Refuge. Threatened species can occasionally be found here, including Steller’s and spectacled eiders. Several arctic goose species frequent the refuge, along with murres, seven species of owls, peregrine falcons, dowitchers, Lapland longspurs and a wide variety of other seabirds, waterfowl, shorebirds, songbirds, and raptors. Refuge staff and volunteers have also documented more than 500 species of plants, demonstrating a high degree of biodiversity for a sub-arctic area.

Let’s talk Togiak’s salmon and trout – catching them on a fly by the score, and keeping it that way

There are five species of Pacific salmon found on Togiak National Wildlife Refuge. All Pacific salmon are anadromous. In the rich ocean environment, salmon can grow rapidly, gaining more than a pound a month. These salmon mature and return to freshwater within two – eight years.

The refuge’s commercial fishery value, estimated to be worth $8,000,000, also has a sport fishery worth $6,000,000 annually. Ensuring that adequate numbers of each fish species are allowed to spawn*[In the case of anadromous salon procreation is external fertilization, where the female deposits the eggs and the male simultaneously ejects milt that contains sperm which fertilizes the eggs] in each drainage is key to this region’s aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

Togiak Refuge also contains prime habitat for several other fish species, including rainbow trout/steelhead [Oncorhynchus mykiss), Arctic grayling [Thymallus arcticus], Dolly Varden [Salvelinus malma], lake trout [Salvelinus namaycush], northern pike [Esox lucius] and Arctic char [Salvelinus alpinus]. Anglers come from around the world for a chance to catch these hearty game fish.

The Salmon Mecca of in “Togiakville”

Common Name Scientific Name Colloquially called

Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) King

Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) Dog

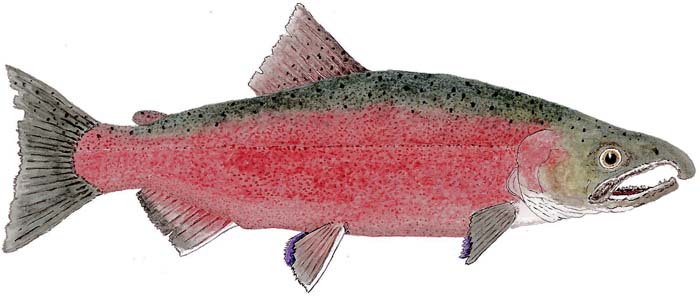

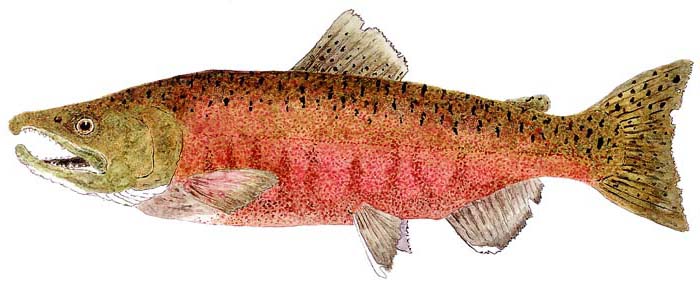

Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) Silver

Pink Salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) Humpy

Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) Red

Sockeye on spawning run in Alaska. Notice the trout visitor waiting for an opportunity to feed on eggs. Sockeye on the spawning run in Alaska. Notice the trout visitor waiting for an opportunity to feed on eggs — Wikipedia Commons image.

Coho (Silver) salmon ocean run colors – Illustration by Thom Glace.

Male coho (Silver) salmon spawning colors – Illustration by Thom Glace.

Great Nutrient Cycle

As salmon grow in the ocean environment, they accumulate marine nutrients, storing them in their bodies. They then transport those nutrients back to their stream of origin when it is their time to spawn, die, and decay. Salmon release their eggs and milt back into the freshwater to re-seed the cycle. Eggs that don’t get buried in the gravel become immediately available as food for other fish, birds, and insects. After spawning the salmon die, and as they decay, valuable nutrients are released. These nutrients fertilize the water that feeds the developing salmon, filter-feeding insects, and aquatic and terrestrial plant life. This process of salmon accumulating marine nutrients and returning them to freshwater streams are referred to as “the great nutrient cycle.”

When they return to spawn, salmon become a veritable conveyor belt for nutrients. For example, an adult chum salmon returning to spawn contains an average of 130 grams of nitrogen, 20 grams of phosphorus and more than 20,000 kilojoules of energy in the form of protein and fat; a 250-meter reach of salmon stream in southeast Alaska receives more than 80 kilograms of nitrogen and 11 kilograms of phosphorous in the form of chum salmon tissue in just over one month.

As the bodies of spawning salmon break down, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients become available to streamside vegetation. According to Robert Naiman of the University of Washington, streamside vegetation gets just under 25 percent of its nitrogen from salmon. Other researchers report up to 70 percent of the nitrogen found in riparian zone foliage comes from salmon. One study concludes that trees on the banks of salmon-stocked rivers grow more than three times faster than their counterparts along salmon-free rivers and, growing side by side with salmon, Sitka spruce take 86 years, rather the usual 300 years, to reach 20-inches thick. — Read more . . .

Natal Spawners

One of the most surprising facts about Pacific salmon is their ability to return to their “natal” or home stream or lake – almost street address accuracy. Scientists now know salmon use a combination of magnetic orientation and memory of their home stream’s unique smell, and a circadian calendar to return to their natal stream to spawn. The memory and smell centers in a salmon’s brain grow rapidly just before it leaves its home stream for the sea. A salmon can detect one drop of water from its home stream mixed up in 250 gallons of seawater. Salmon will follow this faint scent trail, with the aid of the other methods mentioned above, back to their home stream to spawn. For more details on what is known and not known . . .

Male chum [dog] salmon in spawning colors. Thom Glace.

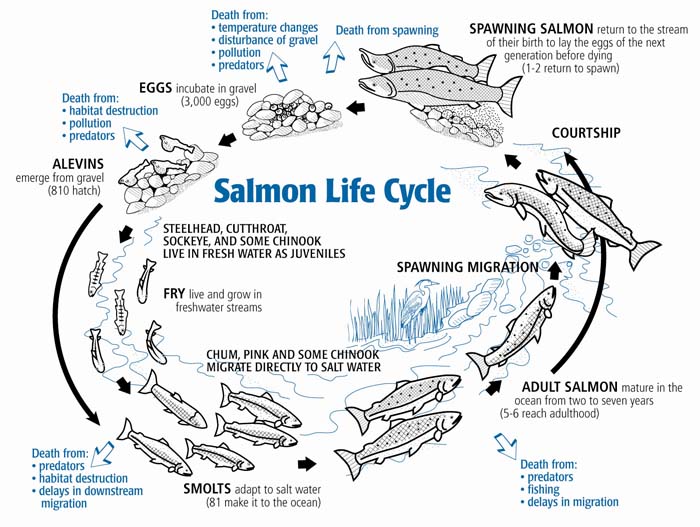

High Mortality

Although a single female salmon can lay 1,000 to 17,000 eggs, very few of those eggs survive from fertilization to maturity. An average of three fish returning for every parent fish that spawns would be considered good production. Many natural and human-related factors cause high mortality. During spawning, eggs may not be fertilized, or may not get buried in the gravel before they are either eaten by predators (birds, mammals, and fish) or become damaged as they bounce along the river bottom. Some eggs may not mature and hatch due to freezing, drying out if the water level drops too low, being trapped in the gravel, or smothered by silt.

Those eggs that successfully hatch to “alevin” stage continue to grow, and then emerge from the gravel as “fry.” Fry becomes subjected to a whole new batch of obstacles and predators since salmon at this stage are near the bottom of the food chain. Pink and chum salmon juveniles head out to sea immediately. The other species may spend as many as two years in freshwater before they head out to sea. During times of these seaward migrations, you can find corresponding concentrations of predators, such as beluga whales, arctic terns, gulls, and other fish species.

Male Chinook [King] salmon in spawning colors. Thom Glace.

Spawning

Salmon reach sexual maturity at two to eight years old. Different species mature at different rates. See below for information on the spawning of each of the five salmon species on Togiak Refuge. When the adult salmon are ready to spawn, after their long journey homeward, they select spawning sites with water flow through the gravel which will provide oxygen for their eggs and carry away carbon dioxide.

Once a female salmon selects a spawning site, she rapidly pumps her tail to wash out a depression in the stream gravel. After the eggs are laid, the female uses the same tail movements to cover the eggs with gravel completely. These gravel nests in which the salmon deposit their eggs are known as redds. Over several days, females may lay several more redds in a line upstream. A single spawning Chinook female can lay up to 17,000 eggs!

Chinook: mature after 3-8 years; spawn July – August in large gravel and deep water with a strong current.

Sockeye: mature after 4-5 years; spawn in August in fine gravel (2-7 cm in diameter) on lake shoals or slack water in rivers.

Chum: mature after 3-5 years; spawn late July – August; spawn in gravel 2-3cm+ and upwelling currents in rivers or some shallow ponds or lakes.

Pink: mature at two years; spawn August – September over coarse gravel and sand, in riffles with moderate to fast currents.

Coho: mature at four years; spawn late September – December; utilize a wide range of spawning sites and currents, often in the farthest reaches of the drainage.

Egg

Although thousands are laid, up to 85% of the eggs can be lost before hatching — the eggs hatch after 6-20 weeks. Hatching times influenced by water temperature, levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide, and vary for the different species.

Chinook: hatching occurs at 12 weeks

Sockeye: hatching occurs after 8 to 20 weeks

Chum: hatching occurs after 8 to 16 weeks

Pink: hatching occurs after 8 to 16 weeks

Coho: hatching occurs after 6 to 7 weeks

Alevin

A newly hatched salmon is called an alevin. At this stage, it looks like a thread with eyes and an enormous yolk sac. Alevin remains in the redd until the yolk sac is absorbed. At this point, they work their way up through the gravel and become free-swimming, feeding the fry. Alevins must have cool, clear, oxygen-rich water to remain healthy. Excessive sediment or extreme water temperatures can kill the fish. Aquatic insects and other fish are an alevin’s primary predators.

Alaskan Coastal Brown bear (Ursus arctos) standing up to better observe a large sow and cubs approaching in the distance. After a false charge by the sow, this young male ran off quickly to leave the creek to the mother and cubs. Photo Alan Vernon September 2007 – commons image.

Fry

Salmon fry may go to sea shortly after they hatch or may spend several years in freshwater. Most species of salmon fry have parr marks (bars and spots along their sides) that act as camouflage to help to avoid predators and hide among the cover provided by rocks, stumps, undercut banks and overhanging vegetation. Parr markings vary for the fry of different species. As the salmon fry grow larger, they move out into more open, faster-moving water. During their freshwater residence, fry feeds chiefly on terrestrial insects. Fry may form into schools during their freshwater residence.

Chinook: fry has bar-shaped parr marks which are larger than the spaces between.

Sockeye: fry have short, oval parr marks, extending a little below the middle of the body; silver in color, with a tinge of blue in the back.

Chum: fry have small, distinct parr marks and slight spots on the body; go to sea almost immediately upon emergence and migrate at night.

Pink: fry has no parr marks (silvery).

Coho: fry have bar-shaped parr marks; rarely have spots on the upper half of dorsal fin.

Smolt

Many physiological and morphological changes occur in a young salmon to help it make the transition from a freshwater to saltwater existence. This process is called smoltification. As the time for migration to the sea approaches, the salmon acquire the dark back, light belly, and silvery coloration typical of fish living in open water. They seek deeper water, avoid light, and their gills and kidneys begin to change so that they can process saltwater. The young fish remain in estuaries and tidal creeks feeding on small fish, insects, crustaceans, and mollusks. They gradually move into deeper, saltier water until they enter the ocean.

Pacific salmon life cycle provided by Skagit Fisheries Enhancement Group.

Life in the Marine Environment

Alaskan salmon can stay at sea for up to seven years, although this varies by species. During their ocean existence, salmon primarily eat fish, invertebrates, and crustaceans.

Salmon can undertake extensive ocean migrations of over 3,000 miles and average approximately 18 miles per day depending on the species. Generally, juvenile salmon from southwestern Alaska streams migrate from the Bristol and Kuskokwim bays through the Aleutian Island chain into the northern Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Alaska. Some salmon populations may use the Bering Sea extensively. Movement of salmon in the ocean is thought to be timed to take advantage of seasonal food availability and ocean conditions.

Salmon are all bright silver while in the ocean environment; however when they return to freshwater to spawn, they undergo many physiological and morphological changes. First, they must switch from using saltwater to freshwater. Returning to freshwater, they change body color from a silver to a brown, green or red depending on the species. The males of some species may change their body shape and develop a hooked snout, humped back, and elongated teeth, which are used to attract a mate and defend spawning territory. Salmon stop feeding once they enter freshwater, but they can travel many miles to spawning grounds by using the stored energy from their ocean residence. All adult salmon die after spawning, and their bodies decay, thus providing nutrients to future generations of salmon.

Resources:

The USFWS Fairbanks Fishery Resources Office’s website “cybersalmon” was the source for much of the above information. Thom Glace Art. Morrow, James E., 1980. The freshwater fishes of Alaska. Alaska Northwest Publishing Company. Anchorage Alaska. Groot, C., and L. Margolis (ed.). 1991. Pacific salmon life histories. University of British Columbia Press. Vancouver British Columbia. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. List of fish species in the Togiak National Wildlife Refuge.