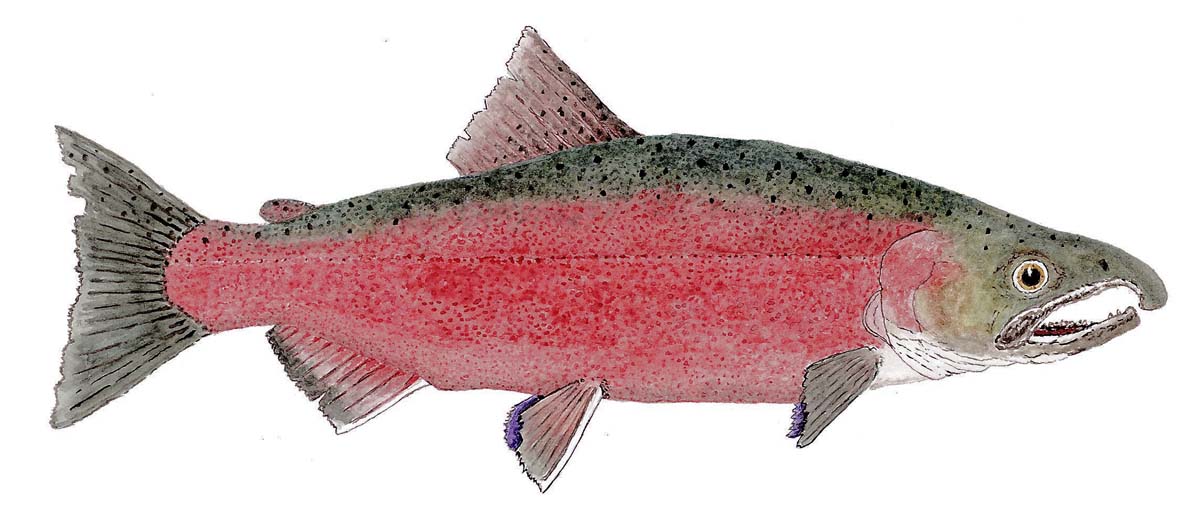

Adult steelhead trout watercolor illustration by award winning artist Thom Glace.

A story about water and anadromous salmons, and steelhead

By Skip Clement with fish Illustrations by Thom Glace

In the Central Valley of California and the Klamath River Basin, the challenge to salvage salmon, steelhead trout, and other anadromous ichthyses is all about water flow, habitat, dams, and water temperature.

In this PART I, we look at the rapid decline of Pacific salmon and steelhead trout from their most southern west coast reaches, California.

Coastal cutthroat trout fresh from the ocean. A Thom Glace illustration.

Resident coastal cutthroat trout. Thom Glace illustration.

California salmon are in dire straits

An unquenchable thirst to re-engineer our environment has transitioned the world’s industrialized nations into comforts unimaginable to our grandparents. Yet, at the same time, according to science, an accompaniment of poorly aimed, clumsily executed plans and actions have supercharged heat and drought experiences tied to global warming worldwide.

Nate Mantua, a climate scientist, leads a team of salmon ecologists and biologists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association Fisheries in Santa Cruz, California, and believes the shutdown would mean higher prices and no fresh local salmon in California this year, 2023. However, it would have little or no effect beyond the region.

Salmon are hardy survivors that have lived on Earth far longer than humans. They migrate hundreds of miles from the freshwater creeks, hatching and then back to the salty ocean and back again, leaping up waterfalls on the return trip. But what’s happening in California and Oregon, at the southern end of the range, scientists say that it might be a harbinger of what’s to come in cooler waters farther north.

“Most of the salmon populations around the Pacific Rim have been doing very poorly” — Dr. Mantua

The assault on California salmon started two centuries ago. First, fur traders wiped out beavers, whose dams created exceptional salmon habitats. Then came the Gold Rush, with hydraulic mining that choked creeks with gravel. Next, settlers drained and channelized the vast California delta and beyond. Next came dams, those engineering marvels that supplied water for a growing population and turned California into an agricultural powerhouse. In the process, California lost about 90 percent of its wetlands.

— By Catrin Einhorn / New York Times / April 3, 2023.

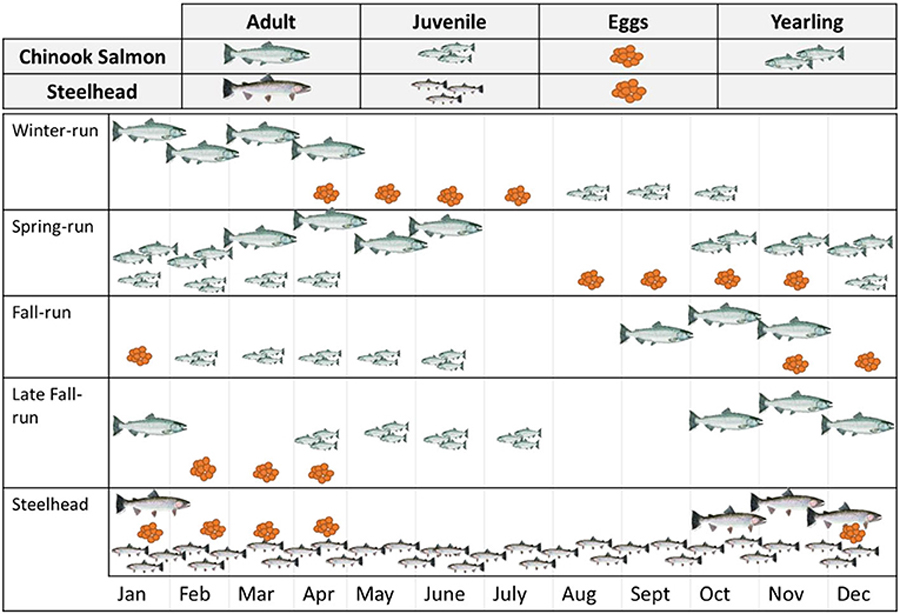

Run timing for salmonids in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers in the California Central Valley. The direction of the fish shows whether they are swimming upstream (headed towards the right) or downstream (headed towards the left). All the adults (larger fish) swim upstream (saltwater to freshwater), while the juveniles (little fish) swim downstream (freshwater to saltwater). Yearlings (medium-sized fish) are juveniles that have spent extra time in freshwater for about a year and grown considerably when they migrate downstream. [NOAA Fisheries]

This week, officials are expected to shut down all commercial and recreational salmon fishing off California for 2023. Much will be canceled off neighboring Oregon, too.

The Central Valley

The ‘Valley’ is known for its agricultural productivity providing more than half of the fruits, vegetables, and nuts grown in the United States. More than 7,000,000 acres of the valley are irrigated via reservoirs and canals, producing 250 crops valued at about $17 billion annually, estimated to be 25% of the nation’s food.

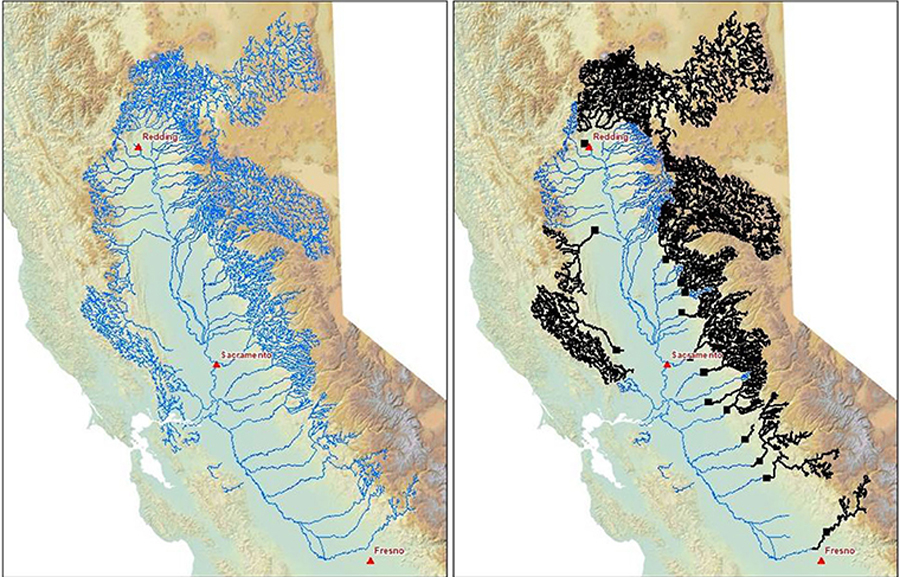

For over six million years, salmon and steelhead (known as salmonids) have returned to the California Central Valley. After swimming under the Golden Gate Bridge and through the San Francisco Bay, adult salmonids swim hundreds of miles up the Sacramento or San Joaquin Rivers. Before dams were built, three of the five salmonid species swam from the Central Valley into high-elevation, cold-water streams within the Sierra Nevada, southern Cascades, and Coastal Mountains range to finish their life cycles—unfortunately, barriers such as dams cut off salmonids from their home streams. When salmonid populations decrease, the effects are felt across the ecosystem—everything from microbes to humans feels the disconnection between the rivers and the ocean. Governmental agencies and their partners are teaming up to restore Central Valley salmonid populations by reconnecting them to their habitats and returning them to high-elevation streams.

The blue lines represent the habitat that was previously available to salmonids in the California Central Valley. The black lines represent habitat that is now blocked by dams and unavailable to anadromous fish. Dams alter downstream water flow and temperatures. (Image credit: NOAA Fisheries]

An alarming decline of fish stocks linked to the one-two punch of heavily engineered waterways and the supercharged heat and drought that come with climate change. There are new threats in the ocean, too, that are less understood but may be tied to global warming, according to researchers.

Scientists and fishers had been braced for bad numbers

Conditions were terrible a couple of years earlier, when the salmon were young and tiny in low, overheated creeks and rivers in California. But as the fish counts came in and the models spit out figures, the numbers were even more dismal than expected. Of all the salmon in California, fall-run Chinook were the last ones robust enough for commercial fishing. But this year, fewer than 170,000 are expected to return to Central Valley rivers. That’s down from highs of over a million as recently as 1995.

Male coho salmon spawning colors. Illustration by award winning watercolorist Thom Glace.

Coho (Silver) salmon ocean run colors – Illustration by Thom Glace.