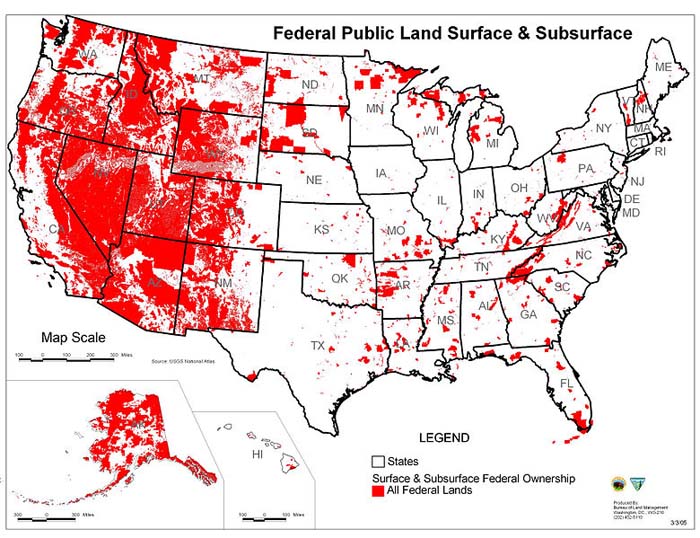

Map of all federally owned land in the United States. Photo by Bureau of Land Management – a commons image

How So Many Western State and Federal Public Lands Became Landlocked

This access challenge has become apparent thanks to recent advances in GPS technology, but the origin of the landlocked problem goes back to the early days of Western statehood

By: TRCP Staff / onX / August 21, 2019

Landlocked Acres by State

Arizona: 1,310,000 acres

California: 38,000 acres

Colorado: 435,000 acres

Idaho: 71,000 acres

Montana: 1,560,000 acres

Nevada: < 1,000 acres

New Mexico: 1,350,000 acres

Oregon: 47,000 acres

Utah: 116,000 acres

Washington: 316,000 acres

Wyoming: 1,110,000 acres

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]his week, the TRCP and onX revealed the results of our latest collaborative study, which showed that 6.35 million acres of state-owned public lands are completely isolated by private lands and therefore inaccessible to American sportsmen and women. To arrive at this total acreage, onX used leading mapping technology to look at state trust lands, state forests, state parks, and wildlife management areas in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

This report also builds on our findings from last year, when onX helped us to identify more than 9.5 million acres of landlocked and inaccessible federal public lands, including those overseen by the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and other agencies.

GPS technology, now accessible to any hunter or angler with a smartphone, has made this access challenge more obvious in recent years. Ours is the first detailed analysis of how big the problem really is, but the jigsaw puzzle of land ownership that has created barriers to public lands where we have every right to hunt or fish has its origin in the founding of the Western states.

Here’s how we got here.

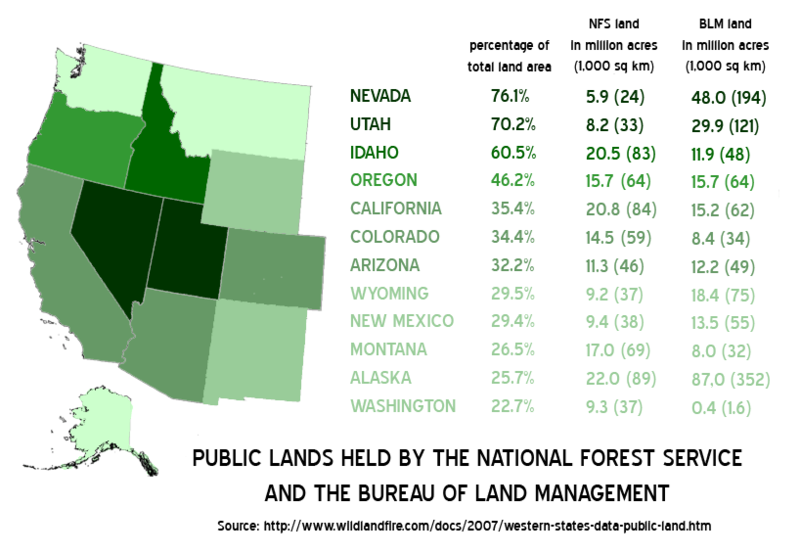

Public lands held by the National Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management in the Western US. A commons image.

State Lands Destined to Be Landlocked

In the 19th century, as Western territories joined the union, each was granted land from the public estate through acts of Congress. These lands were to be used to generate revenue that would support public institutions, most often schools, in the new states.

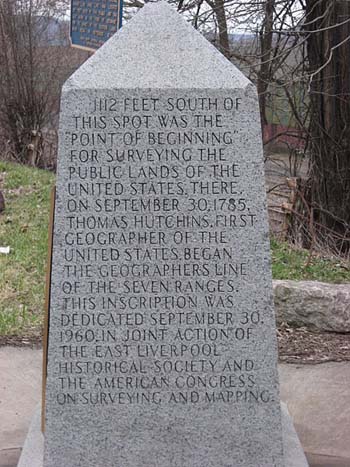

The Public Lands Survey System was used to plat landscapes into six-by-six-mile squares known as townships, each including 36 individual one-mile–square sections. And the enabling acts that established statehood specified individual sections from each township’s grid that would be withdrawn from the federal estate and granted to each new state.

The size and placement of these allotments varied and became increasingly more generous as new states were admitted to the union. For instance, Congress granted Montana and Idaho sections 16 and 36 of each township, while New Mexico and Arizona received sections 2, 16, 32, and 36. The result was a scattered, arbitrary pattern of trust lands that frequently led to sections of state land surrounded entirely by private holdings.

While land exchanges, sales, and acquisitions have consolidated and altered the ownership pattern of state land holdings over the years, the original patchwork is still evident across much of 11-state region that onX helped us study to identify landlocked state lands where hunting and fishing opportunities are being lost. Now home to 38.8 million acres of trust lands, the states have—we learned—a 6.35-million-acre landlocked problem.

View of the Pennsylvania side of the Beginning Point of the U.S. Public Land Survey, a monument marking the site that served as the basis for the entire Public Land Survey System — the system by which most of the United States, outside of the original colonies, was surveyed. Located on the Ohio/Pennsylvania border east of downtown East Liverpool, Ohio, it is split between the city of East Liverpool and the borough of Ohioville in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. Erected in 1881 by a joint commission of Ohio and Pennsylvania surveyors, the monument was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1966. The road on which it lies is Ohio State Route 39 and Pennsylvania Route 68. Nyttend – a commons image.

How Federal Public Lands Became Isolated and Checkerboarded

When it comes to the 9.52 million acres of landlocked federal public lands, these parcels are also a product of history, rooted in the federal government’s aggressive land disposal policies of the 19th century. For much of America’s past, Western lands served as a source of in-kind revenue for the federal government, used at the will of policymakers to achieve their desired aims.

To facilitate the extension of commerce and settlement across the continent, Congress granted railroad companies ownership of alternating sections of land on either side of the tracks, fracturing the landscape into the public-private checkerboard pattern familiar to any Western hunter. The rationale behind this policy was that development spurred by the railroad would double the value of the remaining public lands, which could eventually be sold—negating the cost of the giveaway by the federal government, while simultaneously driving private enterprise.

Meanwhile, as the public domain was divided up piecemeal through the Homestead Act, public lands that had little economic value went unclaimed, and frequently became closed-in by adjacent private holdings. In other instances, some enterprising Western settlers accumulated so much land that public tracts were entirely surrounded by individual ranches or walled off against natural features, like rivers and impassable terrain.

Later, the abandonment of homesteaded farms and a high-profile railroad land scandal returned millions of acres of generally isolated and disjointed tracts of land to the Department of the Interior. The idea of a permanently maintained system of public lands did not take hold until the turn of the twentieth century, when a dedicated model of conservation was championed by the likes of Theodore Roosevelt. It was not until decades later, in 1976, that the Bureau of Land Management, the nation’s largest land management agency, shifted fully to a policy of land retention.

Now, we know better than ever before that these resources play a vital role in maintaining a vast $887-billion outdoor recreation economy, and Americans value our public lands as a means of escaping crowded cities and schedules. In fact, there is a growing need to open overlooked and off-limits public lands to the general public.

Dalton Highway in Alaska. Photo by Bob Wick, Bureau of Land Management – a commons image.

A Quick Word About the Biggest Difference Between State and Federal Lands

It’s important to know that state trust lands differ from federal public lands in how they are managed. By and large, federal lands administered by agencies such as the BLM and U.S. Forest Service are managed for multiple uses, including outdoor recreation, wildlife habitat, energy development, grazing, and timber harvest. The federal agencies are required to balance these uses, and financial profit is not a driver of management.

Under the terms of state land grants, state lands allotted by Congress through the General Land Office were to be managed to produce revenue for designated beneficiaries. This is why, early on, the young states sold off millions of acres of state trust lands for short-term payoffs.

The extent to which states disposed of their lands has varied, with Nevada selling off virtually all of its original land grant and Arizona selling very little. While land sales still do occur with greater frequency at the state level than the federal level, state land boards have moved management direction towards the longer-term approach of leasing them to private interests for grazing, mineral development, and timber extraction. However, to this day, state land boards and management agencies remain obligated to produce revenue for designated beneficiaries, balancing maximum immediate return with the sustainability of revenue and natural resources over time.

This became a hot talking point at the height of the public land transfer debate in 2016, when an extremist minority suggested that the nation’s public lands might be better off in state hands. While this idea still exists, sportsmen and women united to make it known that large-scale transfer or disposal of public lands is extremely unpopular and an irresponsible management strategy. Now, our fight has become more about solving access and management challenges on these lands.

Photo by TROUTSTER – a commons image.

A Solution with Bipartisan Support

One key to unlocking both state and federally owned landlocked lands is robust investment in the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Many have recognized the power of the LWCF to open and expand access to federal public lands—which is perhaps part of the reason why our lawmakers permanently reauthorized the program in a milestone victory for outdoor recreation earlier this year.

But did you know that 40 percent of the program’s funding must be directed to individual states? This is done partly through matching grants to states and local governments for the acquisition and development of public outdoor recreation areas and facilities. In fact, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, more than 40,000 individual grants and $4.1 billion have been provided to states and localities for these purposes.

LWCF state dollars can be directed toward unlocking state lands for recreational access right now. And this purpose could be prioritized in State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plans, which each state must develop and revise every five years to receive LWCF funding allocated to state-initiated projects.

In the meantime, sportsmen and women should be vocal about the need for full annual funding for the LWCF at $900 million—collected from federal offshore oil and gas royalties, not taxpayer dollars. This would maximize the ability for the states and federal agencies to unlock lands for public recreation with LWCF funds.

CLICK ON IMAGE Take action with our simple tool to support legislation that would make this investment in the future of our hunting and fishing access.

Read original TRCP story . . .