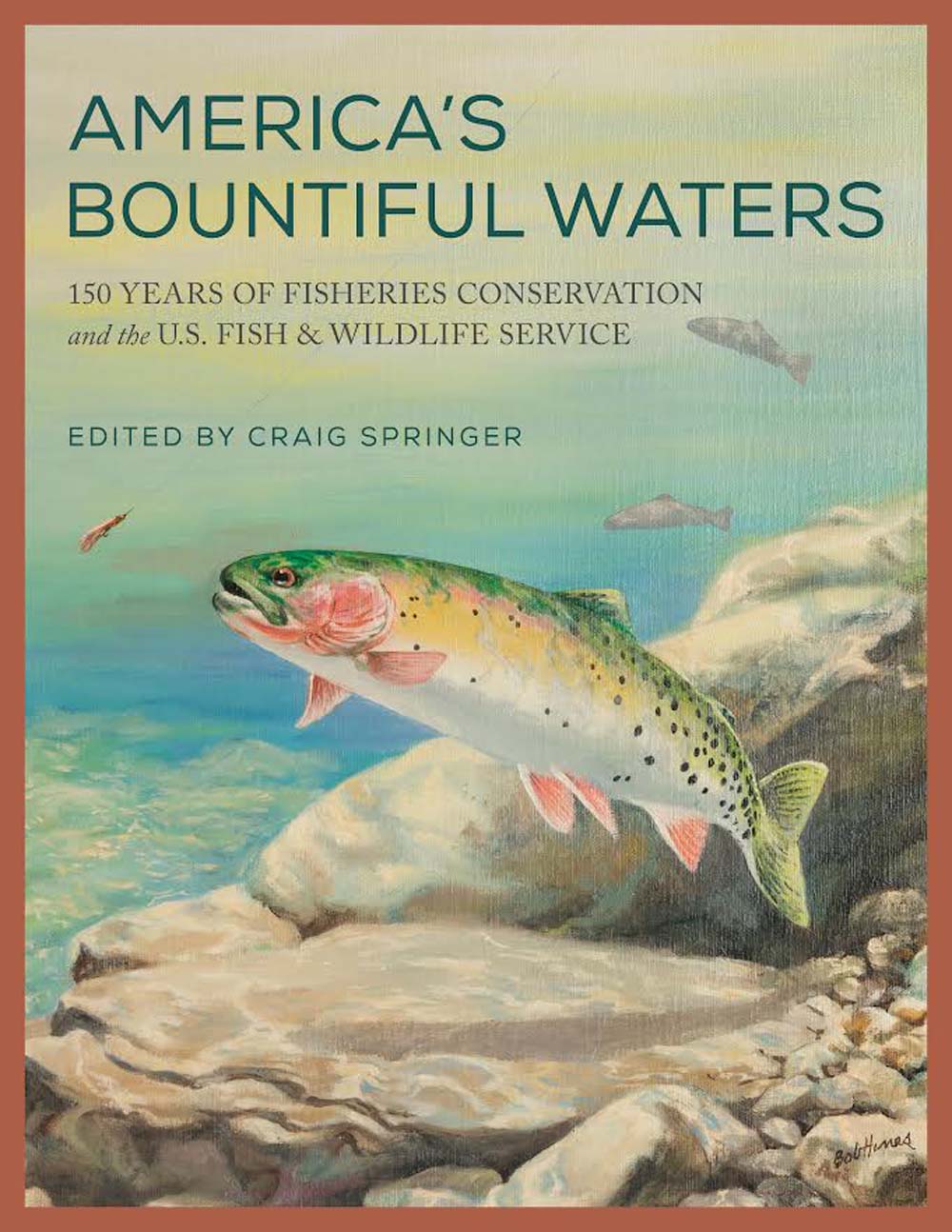

A new classic American book.

‘America’s Bountiful Waters: 150 Years of Fisheries Conservation and the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service,’ by Craig Springer

Writer Craig Springer is with External Affairs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Southwest Region. He lives in Santa Fe County, New Mexico, with his wife and children. He writes about history, nature, the out-of-doors and rambling the American Southwest. Setting is Pecos Wilderness, New Mexico. Photo: Ava Springer

By Skip Clement

Last Saturday, August 14, 2021, the book America’s Bountiful Waters arrived. It was edited, compiled, and author contributed to by a professional acquaintance, Craig Springer.

The cover and size of the book suggested a coffee table opus. I opened it to flip-scan it for a few minutes before heading to a friend’s pond to fill a bucket with black crappie for dinner. But . . .

. . . A few hours later, I was on page 64, Gila Trout and stopped there to catch my breath

I decided to save a portion for bed and the balance for Sunday morning’s deluge Hurricane Fred promised. It’s always a pleasure to read good writing and get to double the joy of reading about the things in life, besides family, that are truly important, fishing and its conservation.

The book incorporates 150 years of fisheries conservation by the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service that began in 1871 as the U. S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries and illuminates its fisheries interventions and species conserved, and therein lies the beauty of the book.

Each species profiled in the book gets introduced to readers differently than they probably are used to – a concise history and then happenstances of how they survived, became stunted, or disappeared because of human activity, right up to today. And, of course, how it came to be that each species crossed paths with the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service. And how, why, and where the service chose intervention.

More about America’s Bountiful Waters?

It’s a classic; the reader witnesses the importance of the service, those who dedicated their lives to it salvaging many of our fisheries – giving up more monetary-driven lives for the sake of the higher goals. The science of the book flows – keeping any angler attentive and eager to turn a page. Also, the book is uniquely riveting to anyone who is species-specific interested, lending to the book’s certain classic rank.

Readers get treated to an insider’s picture of the different species’ dilemma, over time, in some of their native environments, like the western cutthroats [Oncorhynchus clarkii], or coordinates of foreign stocked fish like brown trout [Salmo trutta] and other native fish repatriated to new settings like steelhead [Oncorhynchus mykiss] in the Great Lakes.

Along with the singular way in which Craig Springer illuminates each species and captures the profiles of the past service members and how they distinguished themselves sparkles with ‘amazing,’ and everything else also demands reading. Here I mean the front matter, principal text, all the way to the back matter.

Here are a few images from Springer’s compendium and a few outtake lines:

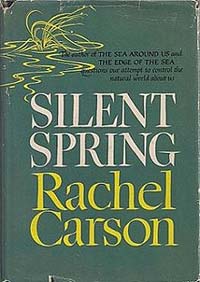

More than six million copies of the book have been sold in the U.S. It’s been translated into some 30 languages. In the Washington suburbs, the house where Carson wrote Silent Spring is now a National Historic Landmark.

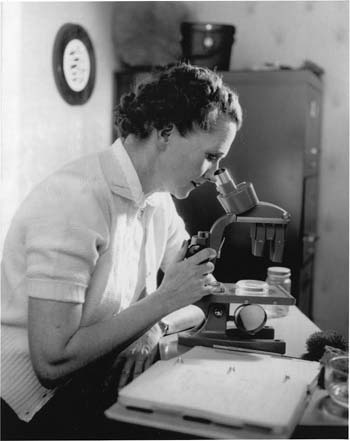

RACHEL CARSON [1907–1964] Pages 151-152

RACHEL CARSON [1907–1964] Pages 151-152

Who, for example, are these science trained people who work so quietly for us at the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service and sometimes so loud in the public spaces of their lives?

One would be Rachel Carson who is best remembered for her pioneering indictment of pesticides, Silent Spring (1962), the book that launched the modern environmental movement. Carson’s sixteen years with the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are now largely forgotten, which is unfortunate because many of Carson’s ideas and writing skills were developed while she was working for the nation’s only wildlife conservation agency.

In addition to being the public relations arm of federal fish and wildlife conservation, Editor Carson was also suddenly exposed to cutting-edge science including troubling new findings on environmental contaminants. The Fish and Wildlife Service’s premiere laboratory in Patuxent, Maryland, had begun to study the effects of pesticides like DDT on certain wildlife, primarily fish and birds. This research had begun early in 1944, shortly after DDT came into widespread use as a chemical to win World War II. As Chief Editor, Carson oversaw all the scientific publications emanating from this new research and, as early as 1945, began considering the topic as a source of an article or book. She was already at work on her second book, The Sea Around Us (1951), a successful bestseller and allowed Carson to leave government service and devote herself full-time to writing. The germ of an idea had been laid, and ten years after she left the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1952 Carson wrote Silent Spring. — Mark Madison, Ph.D.

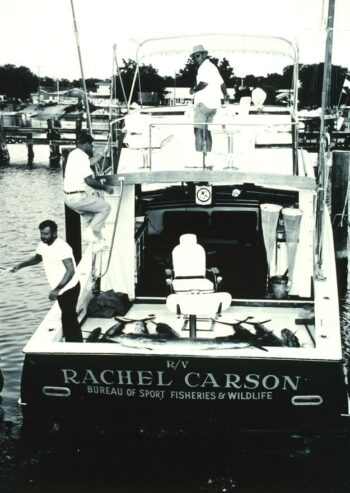

Sailing for Science-Fisheries Research, Supply, and Patrol Vessels. Notice the owner name.

DR. JAMES HENSHALL [1836-1925] Pages 209-211 / SMALLMOUTH BASS Pages 211-215

Dr. James Henshall and I had common experiences with smallmouth bass. We both caught our first on an Independence Day outing in southwestern Ohio—120 years apart.

Henshall caught his in the Little Miami River. He and a pal on break from medical school in 1855 went by train to the little town of Morrow, thirty miles northeast of his Cincinnati home. He documented the outing at length in his Autobiography. Fishing with live minnows, Henshall remembered:

Four Mile Creek, Ohio. “I cast again toward the flat rock, and when the minnow floated to the end of its tether I began reeling as rapidly as I could when the bass made a vicious lunge and seized the bait. Then followed a battle that I will never forget, so vividly was it impressed on my senses. His quick rushes and sudden twisting and turnings reminded me of the brook trout of the Pennsylvania hills; but his frantic leaps and violent shaking and whirling of his strong body in mid-air, with wide open mouth and the rotary play of his powerful tail were characteristic, unique and unequalled.”

I caught my first smallmouth bass some forty miles north of Cincinnati near Oxford in Four Mile Creek while on a family picnic. I was twelve years old. — Craig Springer

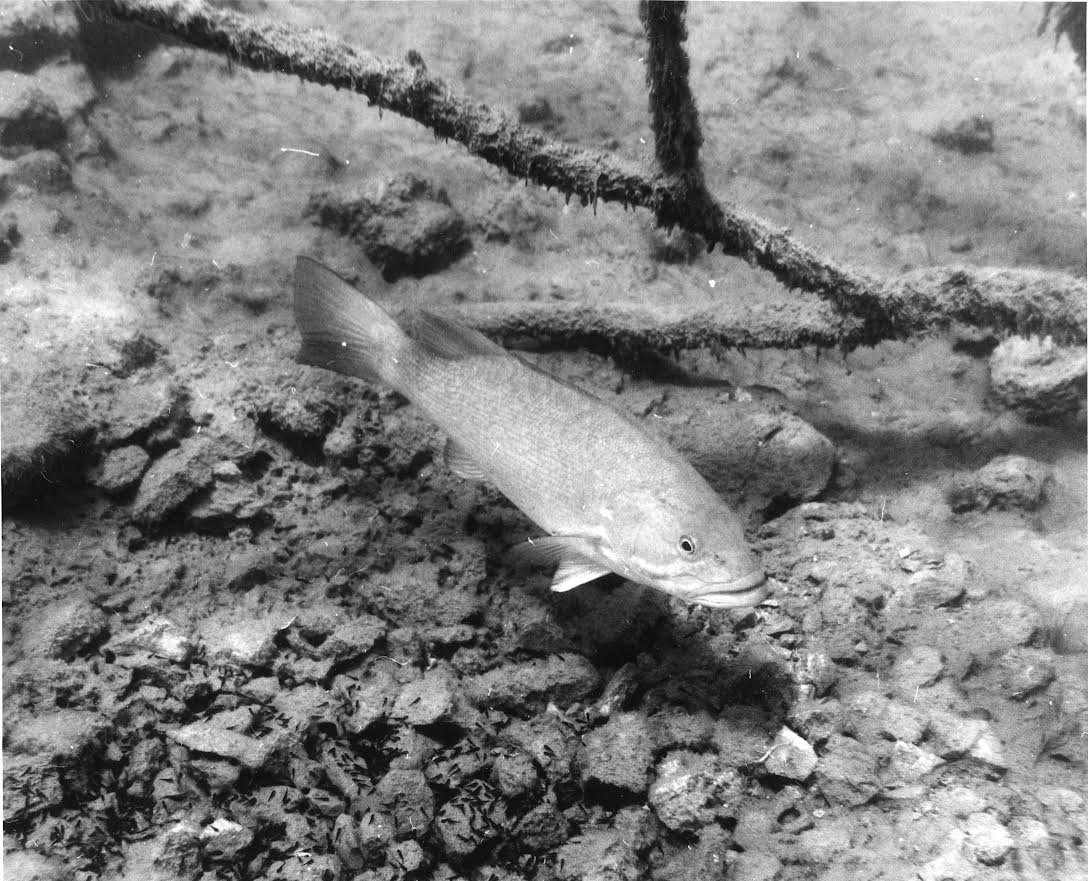

Male smallmouth bass have a strong paternal instinct. They guard fertilized eggs and newly hatched eblack fry seen here wafting over the nest. Smallmouth bass nest over clean gravel in shallows along edges of creeks often near a boulder, log, or overhanging tree limbs, all of which some protection against predators. USFWS MA. NOTE: The smallmouth bass [Micropterus dolomieuis] is potentially the toughest fighting freshwater fish in North America, and is commonly the targeted species in freshwater fishing.

During the day, the bass stayed on the edge of faster water, letting the groceries come drifting to them. At dusk and dawn, the fish went on the prowl into crayfish habitat, hunting prey—a behavior that lasted only until full daylight or until complete darkness fell upon the water.

What I discovered about their nocturnal behavior was most unexpected given that I had caught a fair share of them on top-water stickbaits after dark. In the cover of darkness, smallmouth bass moved into the shallowest and slowest flows to rest, hiding in logjams, wedging themselves in rock crevices, and even moving into slack water next to the bank beneath alder trees, their backs mere inches from the surface.

In the 112 years between Henshall’s Book of the Black Bass and my master’s thesis, a lot of hefty work went into smallmouth bass conservation in the U.S. Fish Commission, U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Smallmouth bass were among the first species of fish transported by airplane in 1928 by the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, flown from Northville Fish-Cultural Station in Michigan to Dayton, Ohio. Fish biologist John van Oosten researched smallmouth bass in the Sandusky area of Lake Erie in the 1920s. Put-in-Bay Fish-Cultural Station in Ohio, produced smallmouth for Lake Erie and points well beyond. Many U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service national fish hatcheries raised smallmouth bass, and some still do, including Genoa, Gavins Point, and Warm Springs national fish hatcheries in Wisconsin, South Dakota, and Georgia.

D.C. Booth Historic National Fish Hatchery & Archives, Spearfish, SD, in cooperation with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, for the benefit and enjoyment of the public.

Not only are these fish stocked for anglers, but they also serve essential roles as host-fish in conserving imperiled mussels in captivity. Smallmouth bass are essential in advancing our understanding of therapeutants in fish culture at our Aquatic Animal Drug Approval Partnership attached to Bozeman National Fish Hatchery—where Henshall coincidentally wrote some of his books. Biologists at our fish and wildlife conservation offices restore habitats by removing blockages to fish passage for the betterment of smallmouth bass and its kind. Smallmouth bass move about, especially in the spring when their instincts turn toward procreation. More habitat means more fish.

Henshall wrote in his Autobiography about catching smallmouth bass in 1856 in the Great Miami River fed by Four Mile and in a stream that laid near the dividing line between Ohio and Indiana. I figure that was Four Mile Creek. I have pondered on the prospect that both he and I waded the same reaches, casting for one more bronzeback—more than a century apart. He was the contemplative sort and I figure that he, like me, had remembrances that rested gentle on the mind.

Smallmouth bass tug the mystic cords of memory. I am calf-deep in Four Mile at the sweeping bend near the old mill next to the Adena earthworks. A car glides down a moraine and crosses the grated bridge, the sound of rubber on the road grows faint with distance. Yellow-breasted chats sing their last in the fading light of dusk in massive sycamores that lean over the bank. Their roots reach into the water in pale gray twisted masses that make dark voids where the fish will lie. As day bleeds into night, that is where the smallmouth bass will head, to the slow water and the protection afforded by the trees. A well-placed floating lure laid in the flat water next to a sycamore, twitched just so, will turn a calm smallmouth bass into an irascible creature sure to remain in memory for decades to come. — Craig Springer

ABOUT CRAIG SPRINGER:

Lockdown and the clan goes fishing. Willow Springer does all the heavy lifting. Here she shows dad and siblings how you catch big rainbows. Craig Springer photo

“I am the son of a decorated Korean War veteran who helped liberate South Korea from the Communists, 1951-52. Dad’s company commander, Capt. Edward C. Krzyzowski, saved the lives of his men in giving his own on Bloody Ridge. For that, he earned the Medal of Honor.

I live in Santa Fe County, New Mexico, with my wife and children where I write about history, nature, the out-of-doors and rambling the American Southwest.

Lockdown brings Carson Springer back from college to cast a fly on the San Juan River, NM. He’s a great fly fisher but, unfortunately, a Packer fan. Craig Springer photo

My work has been published by ESPN Outdoors, Farmers’ Almanac, New York Times, Ohio Magazine, Outdoor Life, Country Living, Colorado Country Life, TROUT, New Mexico Magazine, Persimmon Hill, Home & Away, Sporting Classics, Cabela’s, Iron Worker, Tennessee Magazine, Wild West, and Women in the Outdoors to name a few.

My work was anthologized in the book, Upriver and Downstream. And I co-authored and edited the book, Around Hillsboro, as a fund-raiser for the Hillsboro Historical Society.

I’ve been a columnist or contributing editor for Grouse Point Almanac, Southwest Flyfishing, and its two sister pubs, Eastern Flyfishing and Northwest Flyfishing, as well as the Albuquerque Journal, and Sportsman’s Guide. I presently write an outdoors and travel column called “Backyard Trails” for Enchantment Magazine.

Ava Springer gets called home because of COVID-19, but she says any ‘Aggie’ can catch a cutthroat. Craig Springer photo

Quick Reference Publishing published my high-quality fish I.D. guides, 30 titles in all, covering nearly the entire country. Joe Tomelleri, “The Audubon of Fishes,” illustrated the booklets. Each guide covers 65 sport fishes you are likely to catch where you live. Five-star reviews prevail, and some readers have found multiple uses for the guides.

My interests meld in my academic background. I earned a B.S. in Fisheries Science at New Mexico State.

University, Go Aggies! and an M.Sc. in Fish Ecology at the University of Arizona. I capped it all off with an M.A. in Rhetoric and Writing at the University of New Mexico, with a thesis on the rhetoric of nature and conservation.

I am a member of the Professional Outdoor Media Association. I have earned excellence in craft awards from the American Fisheries Society, the Outdoor Writers Association of America, and the Southeast Outdoor Press Association.”

READ MORE SPRINGER – RIO GRANDE CUTTHROAT: ARTIFACTS OF EPOCHS PAST