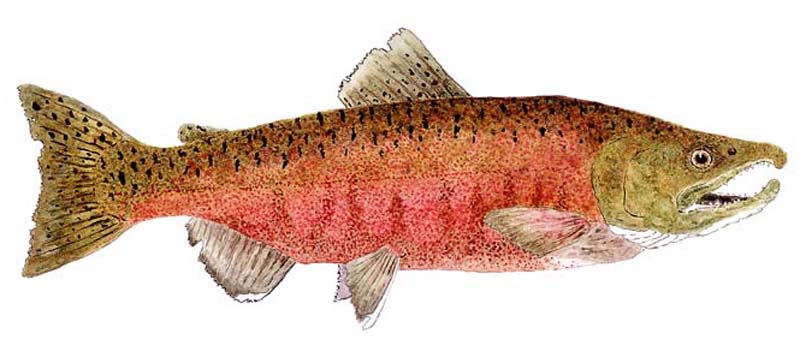

Chinook salmon – NOAA Fisheries image.

A genetic discovery may help restore chinook salmon to reopening river habitats

By Steve Murray / Hakai Magazine / September 4, 2020

The following is excerpted from the subject magazine article – scroll down and click on Read More to view the complete story

Four aging dams on the Klamath River are coming down. Their completion between 1921 and 1964 brought hydroelectric power to Northern California. It also blocked hundreds of kilometers of fish habitat, causing chinook salmon to effectively disappear from the upper river basin. But the removal of dams is no guarantee the fish will return, so a team of wildlife researchers hopes it can coax the fish to repopulate the river by exploiting a new discovery about salmon genetics.

The Klamath was once the third-largest salmon-producing river in the United States, and its fish are still prized by Indigenous tribes that live along its winding path.

Though dam removal has yet to begin—that won’t come for at least another year—John Carlos Garza and Anne Beulke are already investigating how to replenish spring-run chinook in the upper reaches of the Klamath River Basin. Garza is a geneticist with the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center and a researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where Beulke is pursuing doctoral studies. Their research was motivated by a mystery of salmon behavior.

People have long recognized spring- and fall-run patterns, but scientists couldn’t actually explain what caused this distinction. “We found these curious patterns again and again,” Garza says, “even though they were the same type of salmon.” Once they acquired the technology to quickly sequence fish DNA, however, the scientists started analyzing the genes of salmon that spawned at different times. “We found a single region in the genome that’s responsible for the difference between early- and late-migrating fish,” Garza says. This led them to wonder whether they could re-create the missing spring-run salmon by crossing fall-run salmon with those that have the early-migration gene.

Male Chinook (King) salmon [Oncorhynchus tshawytscha] in spawning colors. Illustration courtesy of award winning watercolorist Thom Glace.

Garza and Beulke are now preparing to apply their discovery. They plan to crossbreed and release hatchery-raised spring-run chinook from the nearby Trinity River with fall-run chinook from the Klamath. When the fish return to the hatchery once more to spawn, they’ll crossbreed them again with more fish from the Klamath. “With every generation, you’ll get fish with a higher percentage of their ancestry from the Klamath River,” he says.

Ideally, Garza and Beulke should begin their project this September to take advantage of the 2020 spawning season. Their work was scheduled to start in March, but stakeholder agencies have been slow to agree. The current pandemic may influence their schedule, too. “I can’t even get into the lab right now,” Beulke says.