American Rivers, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group dedicated to protecting wild rivers, has stated the Klamath River restoration project is arguably one of the most significant dam removal projects in U.S. history. 2016

‘There goes me horse, gone’ [Newfoundland saying it’s too late when the barn door was left open]

By Skip Clement

The planned demolition of dams on the Klamath River in the Pacific Northwest hailed as an environmental triumph, might come too late to save Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, the largest species of Pacific salmon and largest in the genus Oncorhynchus.

The plan, doing the right thing finally – may have been too long in coming and instead, a bellwether of an epic loss, even a biblical extinction of the once most productive King Salmon river systems in the world.

Record drought and a monster wildfire this summer have decimated the Chinook salmon that the dam removal was supposed to save and local Indigenous tribes depend on. Many experts are worried the salmon could be nearly gone by the time the dams are set to come down. An outbreak of a deadly parasite, accelerated by climate change, killed most juvenile salmon in the river this year.

IGFA Tippet Class World Record [71 lb 8 oz] Rogue River, Oregon-October, 2002. Above image, Chinook salmon fresh from the ocean. Below, Chinook in spawning colors. Illustration by world-renowned watercolorist, Thom Glace – used with permission.

“The Klamath salmon are now on a course toward extinction in the near term.” — Yurok Tribe, whose culture and diets revolve around the salmon.

On the Klamath, Dam Removal May Come Too Late to Save the Salmon

The planned demolition of dams on the Klamath River was expected to help restore the beleaguered salmon on which Indigenous tribes depend. But after a record drought and wildfire this summer, many are worried the salmon could be all but gone before the dams come down.

By Jacques Leslie / Environment 360 – Yale School of the Environment / September 28, 2021

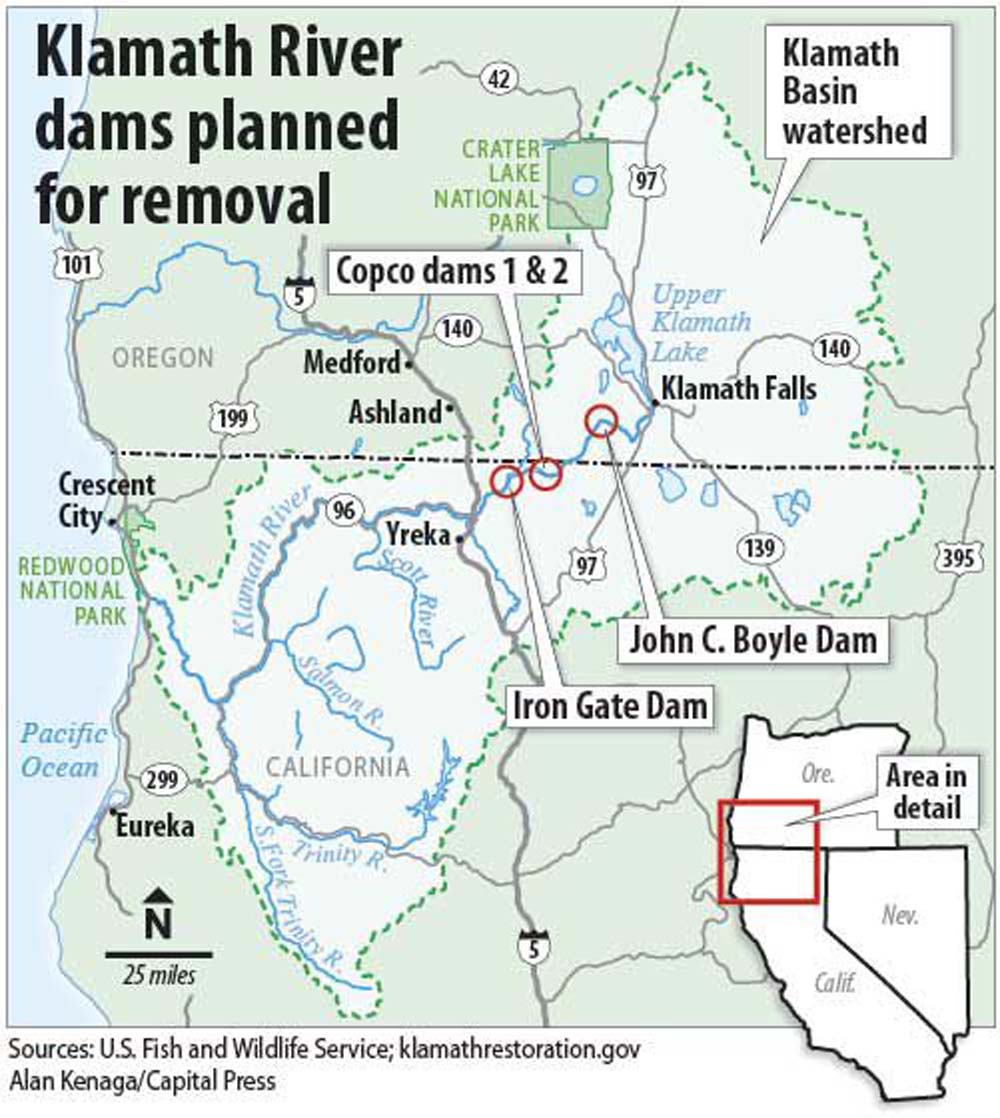

The removal of four obsolescent hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, expected in 2023 or 2024, should have been an occasion for celebration, recognizing an underdog campaign that managed to set in motion the biggest dam removal project in American history.

But that was before the basin’s troubles turned biblical

The main reason for removing the dams is that they have played a major role in decimating the basin’s salmon population, to the point that some runs have gone extinct and all others are in severe decline — and the basin’s four Indigenous tribal groups, whose cultures and diets all revolve around fish, have suffered as the fish have dwindled. But this year the basin has experienced so many kinds of climate-change-linked plagues — a paradigm-shattering drought, the worst grasshopper infestation in a generation, and a monster fire — that it’s uncertain whether the remaining salmon will survive long enough to benefit from the dams’ dismantling.

- “The Klamath salmon are now on a course toward extinction in the near term,” Frankie Myers, vice chairman of the Yurok Tribe, whose reservation covers the Klamath’s last 45 miles to the Pacific Ocean, declared in April. That was in response to the presence below Iron Gate Dam, the dam farthest downstream, of an infectious parasite called Ceratonova shasta whose spread was accelerated by climate-change-driven high water temperatures and low flows. In March C. shasta killed most of a year class of juvenile salmon making its way downriver. One sample found that 97 percent of tested juveniles were infected and 63 percent were expected to die. All the more ominous, those statistics didn’t take into account fish that had already died.

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory researchers are finding ways to maximize the amount of electricity from hydroelectric dams and minimize the danger these dams cause to migrating Chinook salmon and other fish.

“When you’re looking at these numbers, as a fish biologist, you’re just thinking, ‘Oh shit, we’re losing them,’” said Mike Belchik, the Yurok Tribe’s senior biologist.

Until white settlers introduced logging, mining, farming, ranching, and the ultimate insult, dams, the Klamath was the Pacific Coast’s third-largest salmon fishery. The disappearance of salmon would harm a vast menagerie of other animals: at least 137 other fish and wildlife species depend on salmons’ heroic life cycle, which ends in a burst of grit and athleticism as they bring upstream the nutrients they’ve consumed in the ocean, then spawn and die. Orcas, brown and black bears, bald eagles, and river otters all depend in one way or another on salmon. The carcasses of these keystone species nourish the river banks’ trees, whose limbs provide shade for juvenile fish and whose roots prevent erosion, a threat to water quality. Take all that away, as is happening in the Klamath, and the result is accelerated, perhaps irreversible, decline.

The water demands of farmers, ranchers, and environmental services are far greater than what the system can deliver.

“Salmon are the underpinnings of everything else,” said Steve Pedery, conservation director at Oregon Wild, a Portland-based environmental nonprofit. “We’ve seen it across the Pacific Northwest — when we start pulling salmon out of the equation, ecosystems collapse in the absence of them.”

The Klamath is merely the hardest-hit of drought-stricken regions across most of the American West; as of late August, 76.4 million Westerners were affected by drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. It’s indicative of the drought’s unprecedented duration and intensity that for the first time the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation declared an emergency at Lake Mead, the nation’s biggest reservoir, now 65 percent empty, and slashed Colorado River water deliveries to Arizona farmers by nearly 20 percent beginning next January. Farmers throughout the West can expect deeper cuts in the near future.

Droughts are common in the Klamath Basin, “but this drought was really different in lots of ways,” Belchik said. “We had 80 percent snowpack in the southern Cascades, so it didn’t even look like a drought at first. But the snow runoff never showed up.” Instead, soil, already dried out by the long-running drought, sopped it up — it swallowed the snowpack.

Image Description: “The salmon industry is one of the greatest resources of Oregon. The coastal streams and the Columbia river, which is shared with Washington, yield wealth to Oregon that reaches several millions of dollars annually. This picture is of Chinook Salmon at a Columbia river cannery. The value of such an industry to the state can be appreciated when we consider that more than 8,000 persons are actually employed in the fishing industry and more than 40,000 are dependent upon it for support. The Columbia River is recognized as the greatest fishing stream in the world. From it have been taken during the past 45 years, salmon to the value of 125,000,000 dollars.” Original Collection: Visual Instruction Department Lantern Slides / Item Number: P217:set 007 020

Deprived of its customary cold mountain water, the Klamath River delivered warm water temperatures and low flows, perfect conditions for the proliferation of C. shasta. The drought left the river system so parched that for the first time the Bureau of Reclamation, which allocates water to the Klamath’s users, had none to distribute — not for salmon, whose survival against C. shasta depends on at least moderate flows; not for the basin’s already-struggling farmers and ranchers, most of whom rely on irrigated water; and, at the bottom of the pecking order, not for two national wildlife refuges that are crucial stopping points for migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway.

Downstream, the Yurok and Karuk tribes, struggling for decades with the disappearance of salmon from their diets and cultures, argued for a release of water — a “flushing flow” — from the upper river that could have swept away a substantial portion of the worms that host C. shasta. But the bureau said it had no water to spare. In fact, the shortage made it impossible for the bureau to meet its legal obligations to provide sufficient water for endangered salmon in the lower river and endangered suckerfish in Upper Klamath Lake and to deliver water to farmers in the upper basin.

Those failures led most of the parties vying for water to sue the bureau or the Oregon Water Resources Department, even pitting tribes against one another, but none of the litigation could overcome the basic fact that there is not nearly enough water to go around. The drought has made obvious what was true long before climate change’s effects began to register: the water demands of Klamath farmers, ranchers, and environmental services are far greater than what the system can deliver.

Chinook Salmon. Photograph courtesy of Michael Humling, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.