The principal trouts of the US: Rainbow [Oncorhynchus mykiss – includes steelhead], brown [Salmo trutta] and the brook Trout, which is in fact a char [Salvelinus fontinalis], and salmons [Pacific and Atlantic] are the highest profile game fish under duress in our rapidly warming climate. Illustrations provided by world famous watercolorist Thom Glace – his website . . .

Fish Fry: How will a warming world impact U.S. freshwater trouts and anadromous salmon populations?

Scientists believe that the nearly 5-degree Fahrenheit temperature increase forecasted for the interior West could reduce the trout habitat by half in this century, sending their numbers into a tailspin.

Most scientists agree that the effects of global warming are starting to show up all around the world in many forms. Throughout America’s Rocky Mountain West, rivers and streams are getting hotter and drier, presenting new challenges for trout already struggling with habitat fragmentation and pollution.

A recent report by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Montana Trout Unlimited (MTU) found that global warming is shrinking cold-water fish habitat, threatening the trout and other fish that depend upon it. Scientists believe that the nearly five degree (F) temperature increase forecasted for the Interior West could reduce trout habitat by half in this century, sending trout populations into a tailspin.

Adult Atlantic Salmon by Thom Glace, award winning watercolorist, dedicated fly fisher, and conservationist,

While declines in trout population are bad for local ecosystems and biodiversity, they are also bad for people—especially sport fishers and those employed by the billion dollar recreation industry. In Colorado, sport fishing contributes $800 million to the state’s economy each year and supports 11,000 jobs. In Montana, angling generates $300 million annually. Trout fishing also brings in big dollars to New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and Idaho. “Hotter temperatures are shutting down our most popular streams during the height of the fishing season,” says MTU’s Bruce Farling. “The closures are becoming an annual event when trout are stressed by warm water and low flows. The implications…are clear: fewer trout and fewer opportunities to fish.”

A U.S. Forest Service (USFS) study found that between 53 and 97 percent of natural trout populations in the Southern Appalachian region of the U.S. could disappear due to warmer temperatures predicted by global climate change models. The three species of trout in question—Brooks, Rainbows and Browns—are already barely hanging on due to road building, channelization and other man-made disturbances.

Sockeye salmon – photo by NOAA Fisheries.

“As remaining habitat for trout becomes more fragmented, only small refuges in headwater streams at the highest levels will remain,” says biologist Patricia Flebbe of USFS’s Virginia-based Southern Research Station. “Small populations in isolated patches can be easily lost and, in a warmer climate, could simply die out,” she warns, adding that Southern Appalachia trout fishing may become “heavily managed.”

“Trout are one of the best indicators of healthy river ecosystems; they’re the aquatic version of the canary in the coalmine,” says NRDC’s Theo Spencer. “This is our wake up call that urgent action is needed today to reduce heat-trapping pollution that causes global warming.”

NRDC is calling for swift enactment of climate change legislation and for limiting logging and road building near trout streams to ensure enough shade to maintain cooler water temperatures. Also, they say, placing fallen trees and branches and boulders into rivers and streams will help provide shelter for fish and create deeper pools that collect cooler water. Keeping pesticides and fertilizers out of watersheds will also improve the quality of habitat and likelihood of survival for trout species facing an uncertain future.

SIDEBAR:

Meet the five North American species of Pacific Salmon

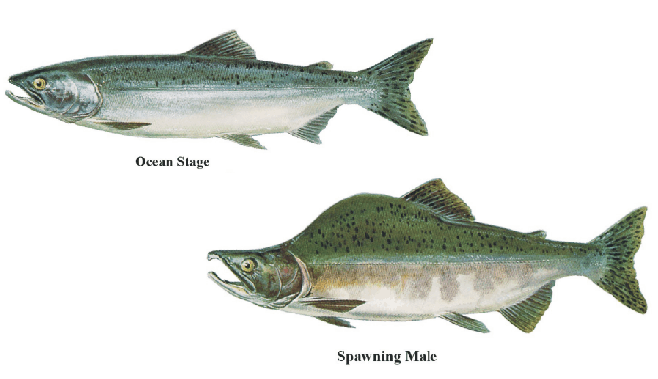

Pink: Oncorhynchus gorbuscha

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

Pink salmon are also known as humpies due to the substantial hump males get just behind the head during spawning. Although they are the smallest species, they are the most abundant in number. They spend the least time in freshwater, spawning in two-year cycles very close to the mouth of streams with little to no upstream migration. While in the ocean, they appear to have steel blue to blue-green backs, silver sides, and a white belly with large oval spots covering their back, adipose fin, and both caudal fin lobes. During the spawning phase, pinks have dark backs with a pinkish wash and green blotches on their sides. These fish generally live for two years, are about 18-24-inches, and weigh about 3-5-pounds.

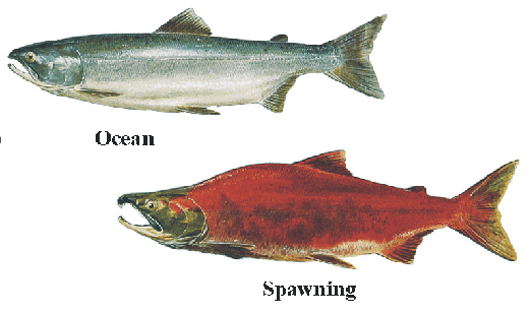

Sockeye: Oncorhynchus nerka

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

Sockeye is the most important commercial species. Sockeye feed on plankton when in the ocean. They have the most significant life history diversity and can spend anywhere from three months to three years in freshwater. They will spawn near shorelines, the bottom of lakes, or hundreds of miles upstream. Fry of this species rears almost exclusively in lakes. While in the ocean, they are greenish blue on top of the head and back, silvery on the sides, and white to silver on the belly. During the spawning phase, the head and caudal fin become bright green, and the body turns scarlet. Landlocked populations of this species are known as kokanee. These fish generally live 2-6 years, are about 21-26-inches, and weigh about 4-7-pounds.

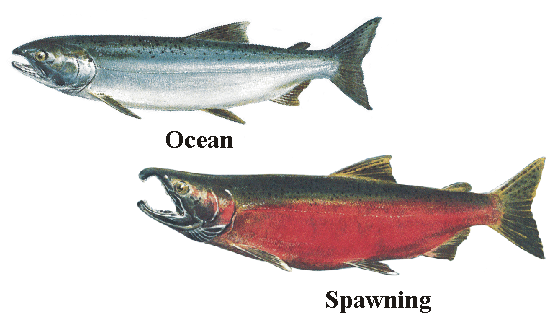

Coho: Oncorhynchus kisutch

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

Also known as a silver, coho are the second least abundant (following Chinook) salmon. While they are one of the most commercially sought after species they make up only 7-10% of the commercial salmon fishery. They spend 1-2 years in freshwater, and prefer near shore feeding grounds. Coho usually travel less then 100 miles from the moth of their stream for reproduction with the exception of a few populations that do travel over a thousand miles. While in the ocean they have dark metallic blue or greenish backs with silver sides and a light belly. They have small black spots on their backs and the upper lobe of the tail. Another distinguishing feature is their gum line which is white. Spawning colors are dark with reddish coloration on their sides. These fish generally live 3-5 years, are about 24-28in in length, and weigh about 5-10 lbs.

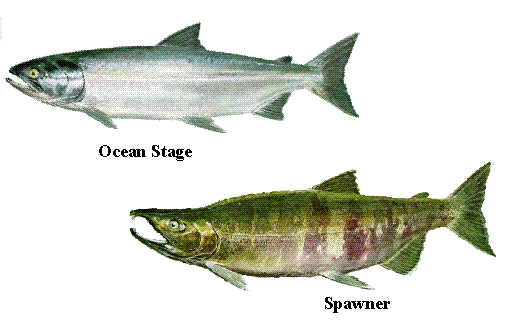

Chum: Oncorhynchus keta

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

This salmon is also known as the dog or calico salmon. Chum comes from a word meaning variegated coloration in the native language. They have the most widely distributed population and the most significant biomass. They are the second largest salmon (following the Chinook). Most populations reproduce near the mouth of their stream. In the ocean, they are metallic, greenish-blue along the back, with black speckles that closely resemble sockeye and coho. During spawning, males get vertical bars in reds, greens, and purples, while females get a black horizontal stripe. These fish generally live 3-5 years, are 21-31-inches, and weigh about 6.5-12.5-pounds.

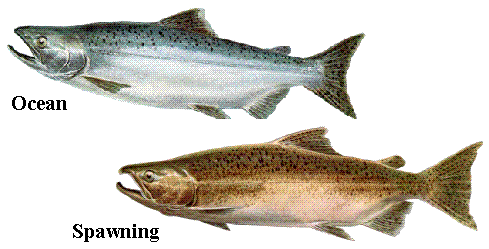

Chinook: Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

Also known as the king, tyee, or blackmouth, the name Chinook came from the native peoples of the Columbia River and is considered a proper name and always capitalized. They are the largest but least abundant salmon. In the ocean, they have bluish-green backs and silver sides with irregular spotting on the back, dorsal fin, and both tail lobes. Another distinguishing characteristic is their black gum line. Spawning colors are olive-brown to dark brown. Males also develop a hooked snout. These fish live about 3-6 years, are 28-40-inches, and weigh about 10-30-pounds. Largest commercially caught over 100-pounds [before dams].

Meet North America’s Anadromous Trouts

Steelhead: Oncorhynchus mykiss

Adult Steelhead Trout by Thom Glace.

They are commonly known as steelhead trout, coastal rainbow trout, silver trout, salmon trout, iron head, or steelie. This species consists of two runs, a winter, and a summer. They differ from other salmon species because they can return multiple times to spawn. However, the number of returning spawners decreases significantly yearly, with few fourth-year spawners. There is a higher mortality rate during steelhead spawning season as they do not feed while in freshwater. They have metallic blue backs, silvery sides, and black spots on the back, dorsal, and caudal fins. Spawning colors are darker, with males having a pink or red band on the sides. They do not have a red dash under the lower jaw, distinguishing steelhead from coastal cutthroat. These fish live about 1-4 years, are about 20- 30-inches, and weigh about 5-20-pounds.

Cutthroat: (Oncorhynchus clarki clarki)

Coastal cutthroat trout fresh from the ocean. A Thom Glace illustration.

Photo US Fish and Wildlife Service

They are also known as sea-run cutthroat trout, coastal cutthroat trout, red-throated trout, sea trout, and blueback trout. This species has three life history options: two types spend their entire lives in freshwater, while only one type is anadromous. A red or orange streak along the inner edge of the lower jaw characterizes cutthroats. They have a greenish blue back tending towards metallic blue, silvery sides, and distinct black spots on the back, head, anal fin, tail, and sides. The spots on the sides extend below the lateral line. These fish live an average of 3-6 years; fourth and fifth-year spawners reach 17- 19-inches and weigh about 1-6-pounds.

Source: Anderson, Genny. “Salmon Species Diversity.” Marine Science. N.p., March 2010. Web. 31 Jan 2012.

Pauley, Gilbert, Bruce Bortz, et al. “Steelhead Trout.” Species Profiles: Life Histories and Environmental Requirements of Coastal Fishes and Invertebrates (Pacific Northwest). 82. (1986): n. page. Print.

Pauley, Gilbert, Kevin Oshima, et al. “Sea-run Cutthroat Trout.” Species Profiles: Life Histories and Environmental Requirements of Coastal Fishes and Invertebrates (Pacific Northwest). 82.11.86 (1989): n. page. Print.e.

CONTACTS: NRDC, www.nrdc.org; MTU, www.montanatu.org; USFS, www.srs.fs.usda.gov

EarthTalk is produced by E/The Environmental Magazine.

SEND YOUR ENVIRONMENTAL QUESTIONS TO: EarthTalk, P.O. Box 5098, Westport, CT 06881; earthtalk@emagazine.com.

Additional Sources:

www.emagazine.com/earthtalk/archives.php.

EarthTalk is now a book! Details and order information at: