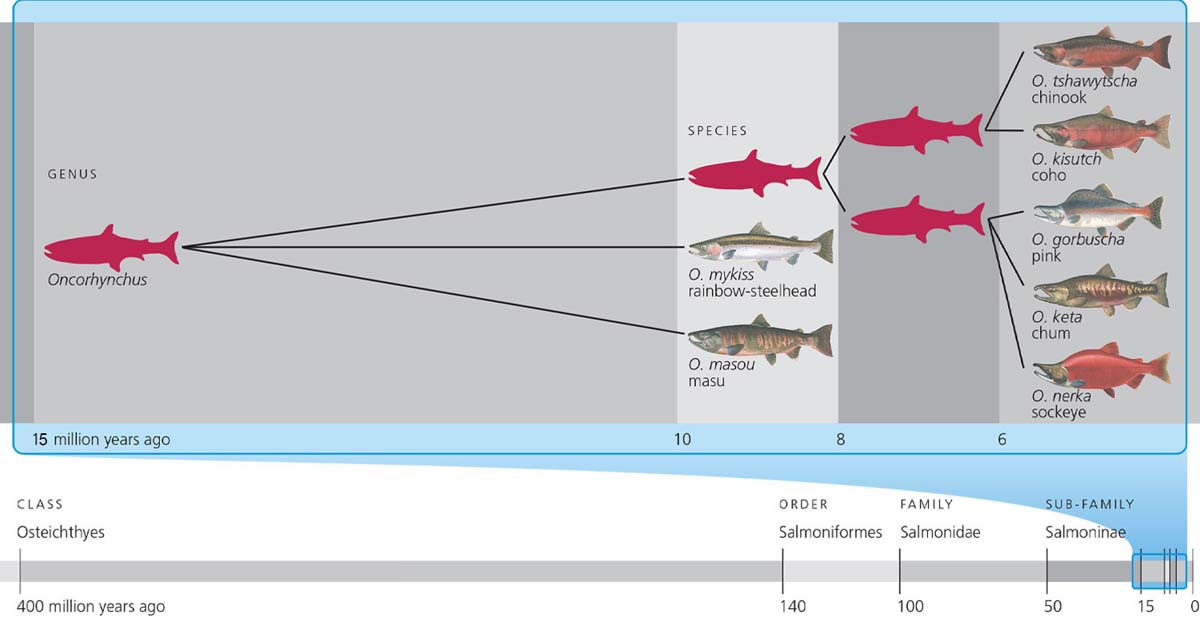

Salmon [Oncorhynchus] family tree

Scientists Are Running Out of Salmon to Study

With west coast salmon populations withering, these researchers are heading for the Great Lakes.

Through years of precipitous declines, Cooke has found it increasingly difficult to study the fish in their native habitat. Now, he’s been all but forced to shift his team’s focus thousands of kilometers east, to Ontario’s Great Lakes.

Male Chinook [King] salmon in spawning colors.

More and more frequently, says Cooke, salmon numbers have been so low that his research permits have been canceled by the federal government or shifted to other watersheds at the last minute. A sudden move can be just as difficult as a cancellation, since the research team does not have any experience, contacts with local Indigenous communities, or even hotel reservations in the new location. This is particularly disruptive for his students, who may only have one or two field seasons in which to collect the data needed for their projects.

“If you’re a master’s student or [postdoctoral researcher], having a year where you plan to do research and then there are no fish is a big problem,” says Cooke. “It’s gotten to the point where it’s not worth it. There’s too much uncertainty.”

Jason Hwang, vice president of the conservation organization Pacific Salmon Foundation, says that marine heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, and habitat loss from urban and agricultural development all make life difficult for west coast salmon. “It’s always a complicated story, and not every population is doing poorly, but the general trend is one of decline,” he says.

Coho [Silver] Salmon Fresh ocean run colors. With permission. Award winning artist Thom Glace.

To avoid the uncertainty on the west coast, Cooke has resorted to studying the migrations of Pacific salmon in southern Ontario. The Great Lakes used to be home to a native population of Atlantic salmon, but it was extirpated more than 100 years ago. In the 1960s, however, hatchery-raised Pacific salmon, mostly chinook with some coho, were introduced to help control invasive species such as alewife. To this day, the lakes are stocked with tens of thousands of Pacific salmon annually to support a thriving sport fishery.

Trevor Pitcher, a biologist at the University of Windsor in Ontario, has studied Pacific salmon in the Great Lakes for the past 20 years, mainly in the Credit River in Mississauga. He says there is almost no distinguishable difference between the fish from the west coast and those in the lakes. “The fish are the same,” he says. “Same size, same behavior; they just don’t migrate as far, and they use the lake instead of the ocean.”

Hopefully, says Cooke, the research done in the Great Lakes can lead to insights that can help Pacific salmon recover in their native habitat. “The salmon are resilient,” says Hwang. “If we give them a chance, they have a powerful potential to recover.”

Read the complete story here . . .