After WWII, Lee Wulff piloted his own airplane, a J3 Piper Cub, from New York to River of Ponds and elsewhere in northwest Newfoundland.

Between the Ponds: Northwest Newfoundland from the 1930s to the 1950s

By Lee Wulff / The Atlantic Salmon Journal / January 7, 2021

In the late 1980s, Lee Wulff wrote a series of first-hand accounts of his explorations of River of Ponds and nearby areas, published in the Atlantic Salmon Journal.

While he began his Atlantic salmon angling there with steamship journeys, during WW2 he flew in a Grumman Goose, as a guide for 5-star General Hap Arnold. Then after WW2 he purchased a J3 Piper Cub on floats, and eventually built several camps in the area for guests.

A River I’ve Loved

NOTE: Excerpted from Part I – Below, click to Read Complete Story

The River of Ponds empties into the Gulf of St. Lawrence far up on Newfoundland’s long northern peninsula. It flows into the sea from a straight shore, offering no safe cove or harbor for boats to anchor in. The only safety for Frank Silver and myself, then, travelling to the river in his “Gertrude”: a 50-footer, was in the tidal pool. We scraped bottom getting in over the bar that protects the pool, and got ready to drop anchor. It was high tide on an August evening in 1941. There was a careless house beside the pool, in which, we’d been told, Sam Shinnicks and his half-dozen children lived. We had scarcely dropped anchor and swung into a balance with the current, when Sam shoved off from shore in his dory and came aboard.

“You’re safe right where you are,” he said, “but if it comes a blow I’ll bring out another anchor for your stern or we can tie lines to each shore. I’m Sam Shinnicks. Be ye salmon fishermen?”

It wasn’t as if he didn’t already know the answer to his question, for his first all-encompassing glance had taken in the rod cases that lay on one of the bunks. He continued, “The river’s low, but there’s some salmon in the pools. Some good ones not far from y’r boat. Ye’ll need guides, I suppose?” We introduced ourselves and nodded.

Atlantic Salmon [Salmo Salar]. The Atlantic salmon is in the family Salmonidae. It is the 3rd largest of the Salmonidae, behind Siberian Taimen and Pacific Chinook Salmon, growing up to a meter in length. Atlantic salmon are found in the northern Atlantic Ocean and in rivers that flow into this ocean. Illustration by Award Winning Watercolorist, fly fisher , and conservationist Thom Glace.

In those days, the long northwestern shore of Newfoundland was served by a coastal steamer and a few schooners which brought supplies to the scattered communities and carried away such things as fish, lobsters and lumber during the open-water months. From December to May the region was served by dog sled or not at all. Visitors were scarce, and Sam was happy to settle in for a visit and, as he had hoped, a drink of Hudson’s Bay 150-proof rum. We talked a bit of salmon fishing and salmon flies. When the small talk was over and we started preparations for supper, Sam left us, saying he’d be back with another guide after we’d had our meal, and we’d talk about the morrow’s fishing.

The dishes were hardly put away when we heard the splash of oars and the scraping of Sam’s dory as he came alongside again. Sam was a robust man, and he wore baggy woolen pants and a heavy fisherman’s sweater. The man who accompanied him was small and dark, with piercing eyes. He wore a weathered suit with his jacket buttoned up. “This,” said Sam, “is Steve ‘ouse.”

Steve sat down, fidgeted for a moment, then reached his right hand to the neck of his coat. With one great stretching movement of his arm, he brought something forth from under his jacket. It was startling. When we could make it out, we saw that his right hand gripped the beak of a great loon, from which hung the bird’s full-feathered skin. In the dim light, the skin seemed almost alive, and it hung down to his shoes.

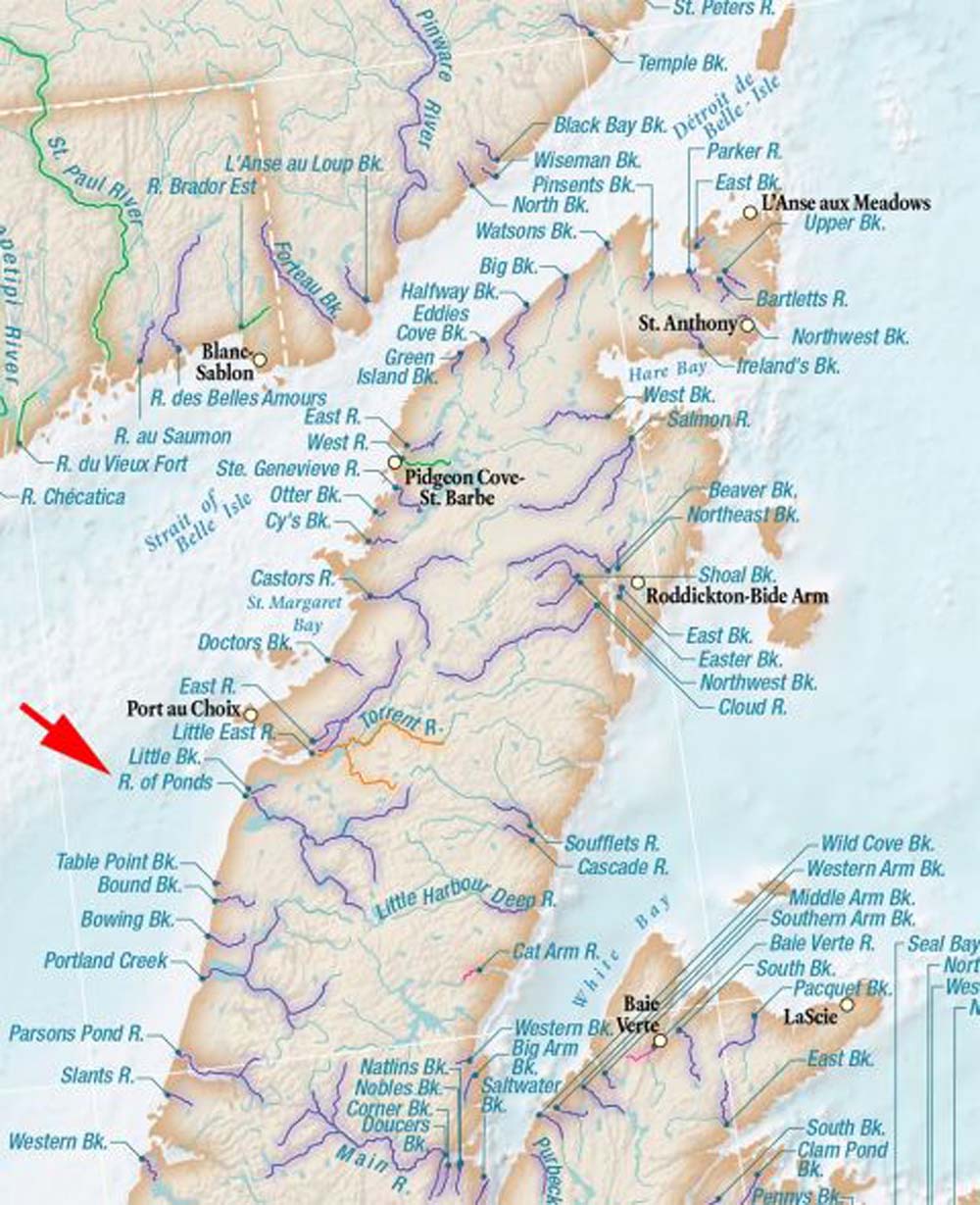

River of Ponds is located on the Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland.

“Are any of these feathers good for flies?” Steve asked. “Sam says ye tie flies.”

The skin was in perfect condition. Every feather was in place and unruffled. Sadly, I told Steve that I didn’t think loon feathers were used in any of the standard salmon patterns, but that I would see if I could make a fly specially for him, using feathers from that skin. We talked on for a bit before arranging a time to begin fishing in the morning. Then they climbed down over the side into the dory, and we heard the quiet splash of oars as they rowed to shore.

I got out my fly-tying kit and set about making a fly. The loon feathers tended to be delta shaped, and were more valuable as cheek feathers than as the main feathers for a salmon fly wing. I compromised by making a squirrel-tail wing, then adding two black and white loon feathers as extra large cheeks. The body was silver tinsel, with the usual golden pheasant crest feather riding on the top and as a tail. It wasn’t much trouble to tie that fly, and it is always good, I feel to bring your guide actively into the pursuit of a salmon—even though you may feel perfectly confident about catching them on your own with your own fly selections.

The pool where we started fishing was just up river from where the boat was anchored. Sam pointed out the spots where he thought a salmon might lie. Steve House was to take Frank to another pool, but they both stood by to watch me cast out the Loon Fly .

I cast and cast and cast, but not one salmon moved for the fly, although several jumped in the area where Sam had said they’d lie, and through which I was fishing. Finally, Frank and Steve moved on, up around a bend in the river, to a pool they called “the Running-out of the stiddy.” When they’d gone I sat down on a big rock, got out a fly box, took out a big number four White Wulff and tied it to the end of my leader. Sam watched me, a look of amazement on his face. Apparently he’d never seen a dry fly before, and never a fly so big, since most of the fishermen on Newfoundland rivers used only wet flies ranging from a size eight up to size four.

Lee Wulff landing his plane.

When he’d recovered from his first surprise, he said, “Big as a sea gull, sir! That’ll frighten them sure!” He was humoring me, I knew. In his mind, no self-respecting salmon would even consider coming near such a monstrosity. I greased the fly, and drifted it lazily over the run where the fish were lying. For a dozen casts it drifted like a sea gull, sitting high on the water, conspicuously larger than the bits of white foam that were drifting along on the surface of the brown, peat-stained river. With startling suddenness, a salmon of about 15 pounds came up under the fly, jaws agape, and took it down.

I heard Sam’s whispered, ” Holy Mother of God!,” as the rod bent down. The reel sang for a moment, then stopped. The fish stayed quiet while I reeled in the casting slack and then, when I built up the pressure a bit, he raced upstream into faster water. “Watch it there, Sir! There’s live rocks under that white water. He’ll foul you ’round ’em.”

He didn’t. He jumped three times. He rolled over in a bath of white foam and spray, and set off downstream, while Sam and I followed along on the shore. He hesitated just a moment at the tail of the run, and then took off again for the sea. Unfortunately, the fish passed on the far side of the anchor line when he came to the “Gertrude”. He slowed down then, and held there while Sam and I scrambled into the dory that was beached on our side of the river. We were halfway out to the boat when the salmon decided to refresh his memory of the salt water, and back to it he went, taking the fly and part of the leader with him.

“Bad luck sir,” said Sam. “But you’ve got another one of them things, I suppose.” I admitted I did, and sat on a log to find it and tie it on. I worked the pool for just over half an hour and caught one grilse, a fairly bright fish that was late-running and fresh from the sea. It put up a good fight. I decided to save the fish for food, and after I’d killed it, I put it into a side pool Sam had built with stones. It would keep cool there until we were ready to take it on board.

Cains River in Northwest Newfoundland on 3-May-2019. The perfect spring fishing-conditions. ASF

Another salmon made a vicious pass at a Jock Scott, but missed it and wouldn’t come back. At mid-morning, we left the pool to move upstream. Frank and Steve were still at the “Stiddy”. They had two salmon of about 10 pounds each lying in the shade. I’d converted Frank to catch-and-release for any fish we didn’t need, but Steve had insisted he needed them badly to feed his family, and that was understandable. I’d seen one of Sam’s youngsters, a little girl of about seven, who’d come down to the pool while we were fishing. Her dress was made from a flour sack, with holes cut out for her head and arms, and with short sleeves added at the shoulders. Newfoundlanders had had a rough time in the depression and the hard times were still hanging on.

Sam and I went on upstream to the next pool. It was at the outlet of a big expanse of water that stretched away for seven miles or more inland. Though the sun was high and bright, and the day warm—not good conditions for salmon fishing—I caught two grilse and a salmon before we decided to go back to the boat for lunch. I had enjoyed fishing that lower section of the river, but now I started thinking about the far off, seldom fished waters that lay above Big Lake. Sam had told me that most of the River of Ponds’ salmon were already across the lake and in the upper river. We were fishing, he said, for nothing but the few stragglers that were still hanging on in the lower river.

Sadly, we had only one day to fish, and while Sam and Steve could have brought a dory up the river, and rowed the seven miles across the lake, there still wouldn’t have been time to get any fishing done as we would have had to make a three-mile hike, over a very poor trail, to reach the fine upper waters. But Sam’s tales of the size and number of salmon in the upper pools set me to dreaming, and made me determined to fish that wild, upper river one day. We had our lunch aboard the boat. For the most part, we breathed the clean, fresh air that came in off the Gulf or out of the forests to the west, but every once in a while we’d get a swirl of wind that brought us a powerful stench of rotting fish.

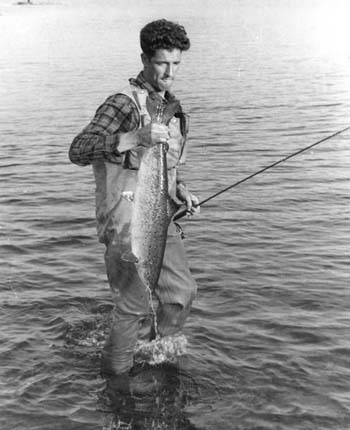

Lee Wulff holding a large salmon, at or near River of Ponds.

Sam was drying cod fillets on racks beside his house. As his family cleaned the fish they would toss the offal on the beach, where the warmth of the sun made it putrid. The smell permeated the air around Sam’s yard, but he and his family never seemed to notice it. Fortunately for us, the wind was from the west, and while we were on the boat or fishing the river, we were up-wind most of the time.

We had a lazy lunch and didn’t fish again ’till evening. An interesting thing happened then. Frank and I had both fished through the pool without a rise, but on my second time through I hooked a grilse. Sam was sitting on a log on the bank and Steve had gone home for the day. Frank was standing beside me in about a foot of water at streamside. I’d pioneered using small, very light fly rods for salmon, and was fishing with a six-footer. With lots and lots of salmon behind me, I was very casual about the grilse I was playing, and I was talking to Frank when I brought the fish in close.

With a sudden spurt of speed, it made a dash that took it right between my legs and on into deeper water. I was so intent on finishing my sentence that when the tip of the rod started to follow the fish I subconsciously passed the rod on through my legs as well and, gripping it again on the other side, continued to play the fish.

Every once in a while after that, when I wanted to surprise someone who was with me, I’d get a salmon I was playing into the legs so that I could pass the rod through after it and amaze the onlooker. That grilse was my only fish for the evening, but Frank landed a 17-pounder just at dark.

“Would ye’ like some fiddlin’ tonight?,” Sam asked. I looked at Frank. He seemed as puzzled as I was. My glance swung back to Sam who made a motion as with a bow on a violin. I smiled then and we both nodded. In due time, Sam came aboard in the darkness with his fiddle. He played the Newfoundland songs like “Lukey’s Boat”, “We’ll Rant and we’ll Roar”, “Kelligrew’s Soiree” and many others. There were occasional pauses for a tot of rum. Sam, it seems, had learned to play from his father, and couldn’t read a note of music. He had a fine sense of rhythm, though, and it was a pleasant thing to sit on the deck on that warm, moonlit night, with a light breeze coming in off the Gulf, and listen to Sam’s fiddle. He could have gone on all night, I believe, but we grew a little weary and, besides, we ran out of rum—which may have dampened Sam’s enthusiasm, just enough. We turned in about 2 a.m.

Lee Wulff was known as a master fly maker, and one who particularly used small flies on light gear to pursue wild Atlantic salmon.

We left in the early morning, catching the high tide to cross the bar. The wind was light and the waves were small, but we got stuck as we tried to cross into the deep water of the Gulf. Fortunately, we were early and the tide was still rising. While we waited for higher water, I got out my fly rod and cast from the deck. Sam had said the salmon wouldn’t take a fly in the salt water, but I thought I’d make a few casts anyway. I put on a big streamer, a number two, with yellow and white hackles and a silver body.

After a dozen casts or more I hooked a salmon. Sam was watching from the beach, and I saw him take off his cap and scratch his head in amazement. Sam walked over toward his dory to come out and get the fish, but when I brought the salmon alongside I reached down and released it. I’d learned that one of the salmon Frank had given to Steve had gone to feed not his household but his dogs. Codfish were plentiful and good enough for that.

The tide lifted us free of the sand that held us. Sam stood beside his dory, disappointed, but waved vigorously when the tide lifted and we slid on over the bar and were on our way.

This is the first in a series of four articles Lee wrote for the “Atlantic Salmon Journal” on the River of Ponds. Master angler Lee Wulff was ASF’s honorary chairman (Can.).

Click Here to read all four parts of this original story by Lee Wulf published by The Atlantic Salmon Federation

Lee Wulff was guide to General Hap Arnold in this salmon angling and cross-country adventure at River of Ponds. Hap Arnold became known as the “father of the U.S. Air Force” for his energetic and effective organizational ability. He was the only man to hold the rank of 5-star general in both the U.S. Army and U.S. Air Force. Arnold addresses four flying schools, the largest group of aviation cadets ever gathered, in December 1942. He promised to boost U.S. aerial combat capability to 10 times that of Axis forces. (Bettman Archive via U.S. Air Force)