Covid: Campsites are full, streams are packed, guides are swamped, and fly shop ownership is the new Bitcoin

Covid: Campsites are full, streams are packed, guides are swamped, and fly shop ownership is the new Bitcoin

At first, I noticed there was no one, then, like a light switch in a dark room, it was July and the outdoors filled with folks who knew very little about their boat, RV, fly rod, stream, spinning rod, fish handling, or surf fishing – many clueless beyond imagination about etiquette.

It got crowded and trashy overnight

My local park sites that were almost always empty mid-week have been blocked for weeks, and empty – sometimes all of the prime sites. I was told on my initial query that they were booked, and parks federal, state, and local have policies that hold spaces for two days.

How reservations work needs to be changed – made easier for all stakeholders

Mixed among the new travelers are those who have figured out the penalty for no show is so small that they book more than one pubic campground site, never cancel, and take the most desirable site that is available. It’s ‘efff’ you structured.

So, a park could look empty and have no sites available. Park management might not care. It’s how it’s been for decades – less work and the money comes rolling in. And then there’s always overbooking too, which is more prevalent with commercial campground operations.

— Skip Clement

The big story is, however, out West where the buffalo roam

Crowds swarm the public lands

Land managers and gateway communities struggle to keep up.

By Jonathan Thompson / High Country News – Print Edition / June 18, 2021

Copied with permission – all images HCN / charts and graphs others as cited in credits.

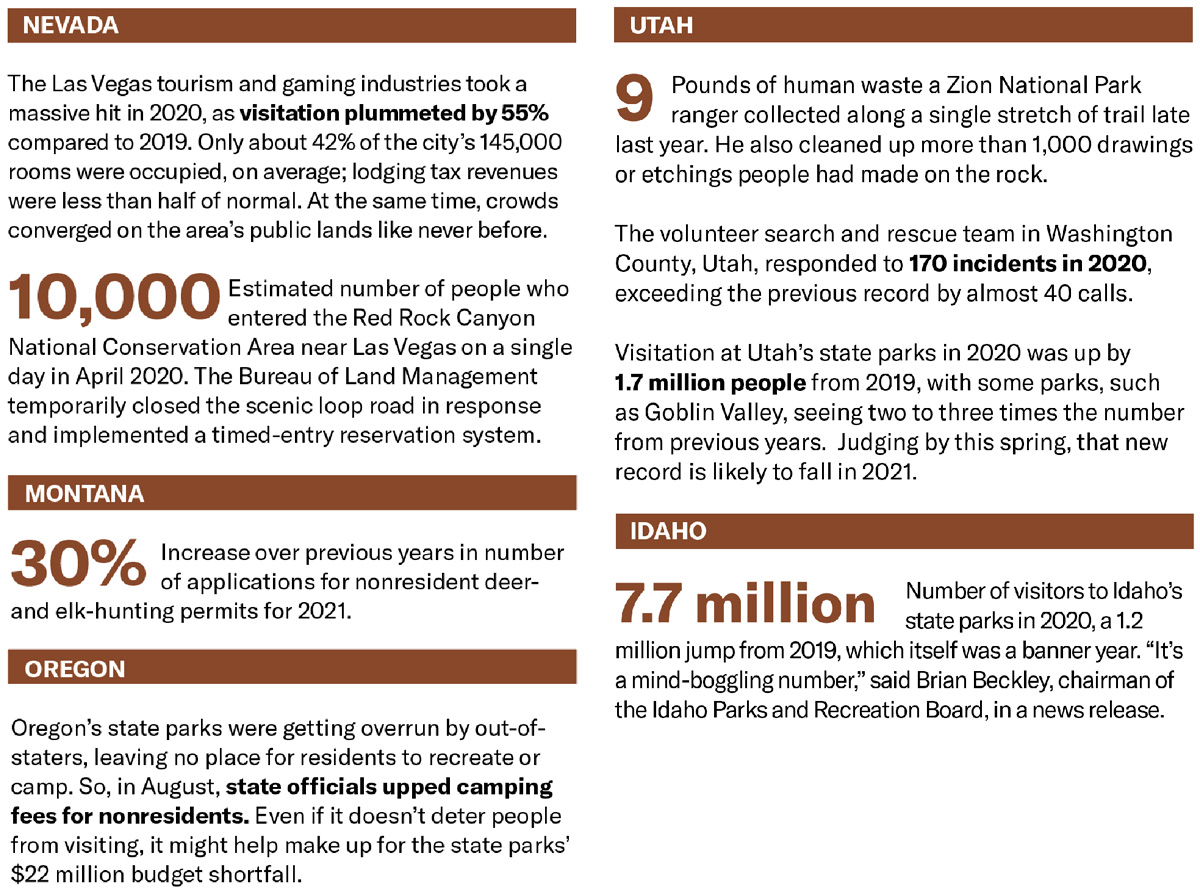

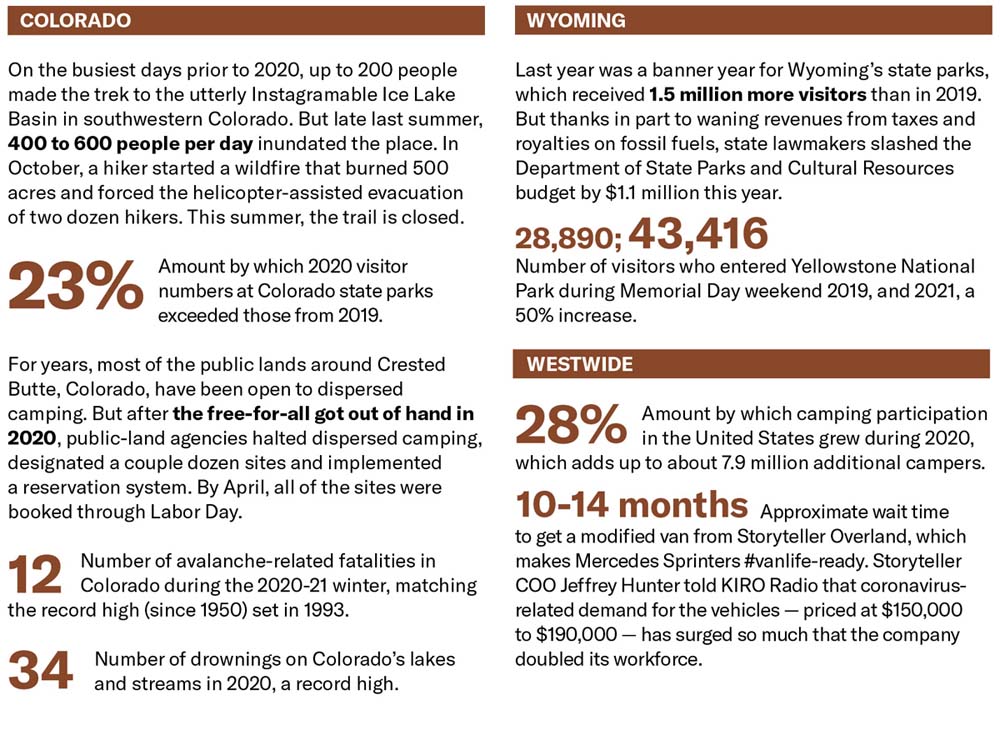

Last spring, as the first wave of measures to halt the spread of coronavirus kicked in, travel screeched nearly to a halt, and the hospitality and tourism industry slowed considerably. Locals in public-land gateway towns predicted doom — and also breathed a big sigh of relief. Their one-trick-pony economies would surely suffer, but at least all the newly laid-off residents would have the surrounding land to themselves for a change.

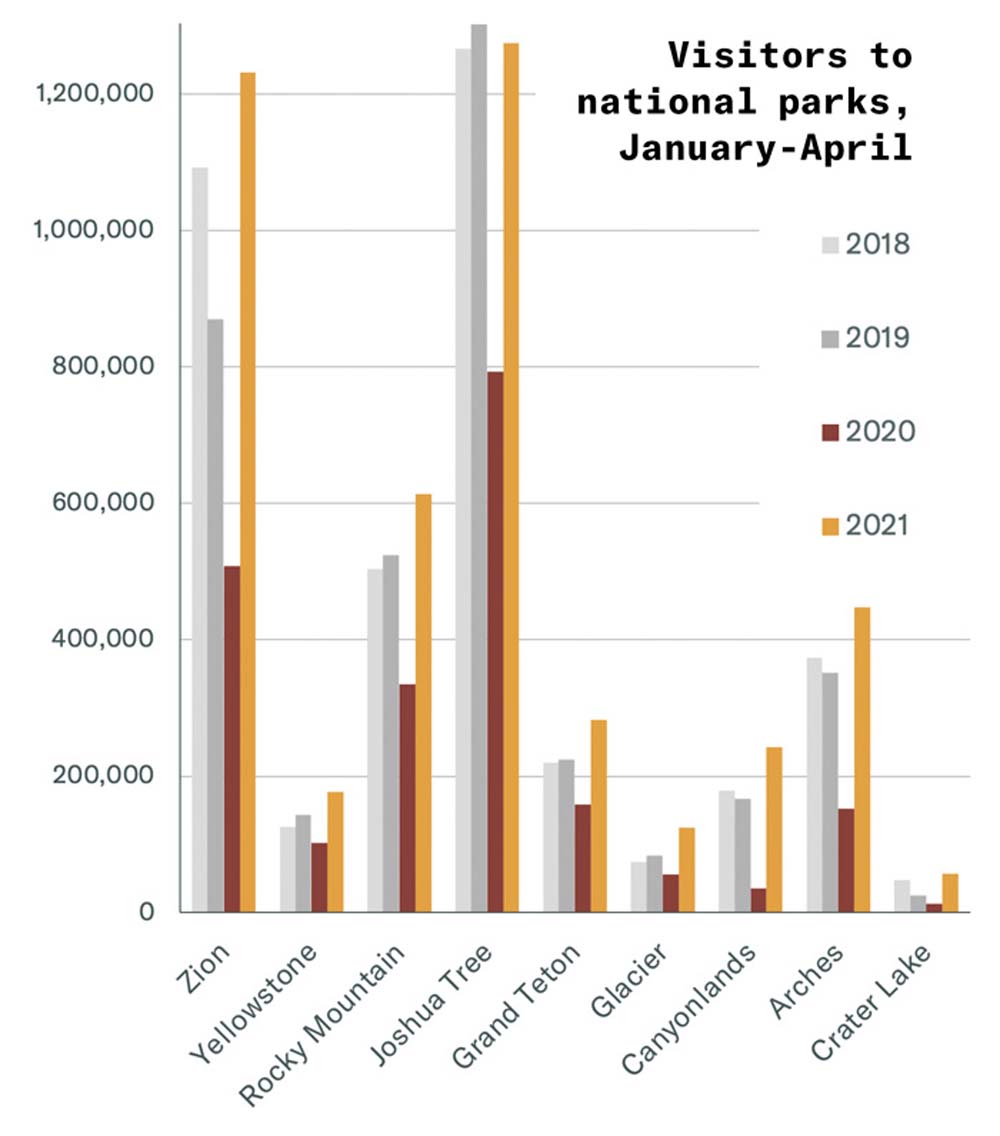

For a few months, the prognostications — both positive and negative — held. Visitation to national parks crashed, vanishing altogether in places like Arches and Canyonlands, shut down for April. Sales and lodging tax revenues spiraled downward in gateway towns. Officials in many rural counties pleaded with or ordered nonresidents to stay home, easing the burden on the public lands. It was enough to spawn a million #natureishealing memes.

Zion National Park, Utah, this May. Bridget Bennett

In the end, however, the respite was short-lived. By midsummer, even as temperatures climbed to unbearable heights, forests burned and the air filled with smoke, people began traveling again, primarily by car and generally closer to home. They inundated the public lands, from the big, heavily developed national parks like Zion and the humbler state parks to dispersed campsites on Bureau of Land Management and federal forest lands.

It was more than just a return of the same old crowds. Millions of outdoor-recreation rookies turned to public lands to escape the pandemic. Nearly every national park in the West had relatively few visitors from March until July. But then numbers surged to record-breaking levels during the latter part of 2020 — a trend reflected and then some on the surrounding non-park lands.

Boulder Creek, Colorado, in 2020. Andria Hautamaki

If nature did manage a little healing in the spring, the wounds were ripped open again by summer

If nature did manage a little healing in the spring, by summer, the wounds were ripped open again in the form of overuse, torn-up alpine tundra, litter, noise, car exhaust, and crowd-stressed wildlife. Scattered human and toilet paper were alongside photogenic lakes and streams. Search and rescue teams, most volunteer, were overwhelmed, with some being called out three or more times a week. Meanwhile, the agencies charged with overseeing the lands have long been underfunded and understaffed — a situation exacerbated by the global pandemic. They were unable to get a handle on all of the use — and increased abuse. There is no end in sight: The first five months of 2021 have been the busiest ever for much of the West’s public lands. And tourist season has only just begun.

Trash hanging from a tree (left) and a sign (right) at a popular dispersed camping area in Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton National Forest, in July 2020.

Ryan Dorgan

Read the original story for more information . . .

Jonathan Thompson is a contributing editor at High Country News. He is the author of River of Lost Souls: The Science, Politics, and Greed Behind the Gold King Mine Disaster. Email him at jonathan@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. Follow @jonnypeace

Sources: National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, Outdoor Industry Association, Wyoming State Parks & Cultural Resources, Colorado Parks & Wildlife, Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, Town of Silverton, Great Outdoors Colorado, Teton County.

Get High Country News and learn what the West thinks . . .