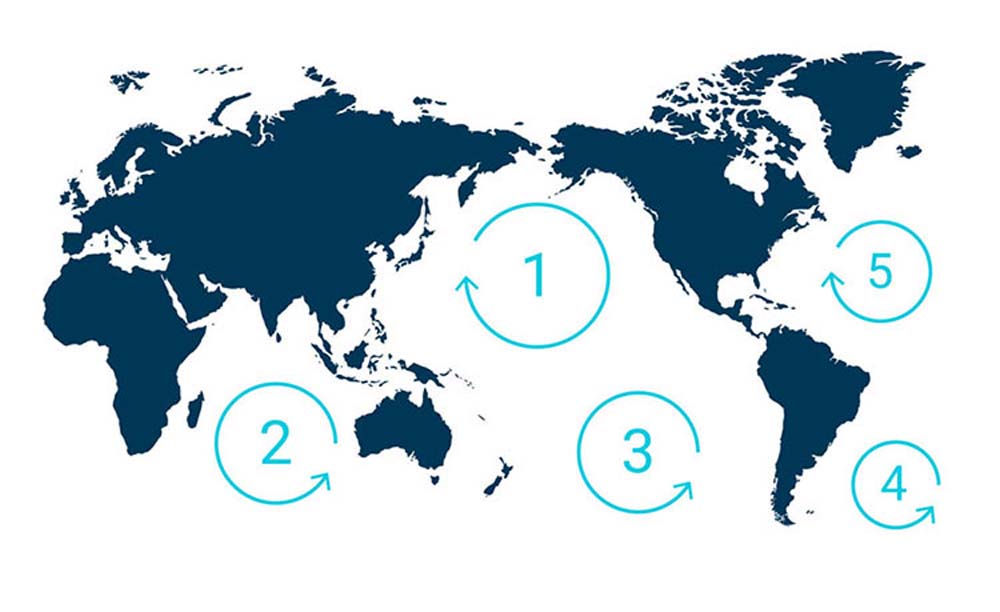

Ocean gyres have been circulating water around the world for millions of years. In recent years though, as well as circulating water around the globe, they have begun to act as trash vortexes, pulling in plastic debris and not allowing it to escape. Notice the rotations.

Scooping Plastic Out of the Ocean Is a Losing Game

Open ocean cleanups won’t solve the marine plastics crisis. To really make a difference, here’s what we should do instead.

A garbage truck turns off the road, engine rumbling, brakes wheezing, and the smell of rot trailing in its wake. The truck stops short and starts to reverse—beep, beep, beeping down a boat launch. With salt water lapping at its rear tires it stops, opens its tailgate, and dumps its load of cups, straws, bottles, shopping bags, fishing buoys, and nets.

A minute later, this plastic waste is floating away on a journey to pollute the ocean and poison the food chain. As the garbage truck drives away it passes another truck preparing to back down the ramp. And another pulling into the marina—one of an endless stream of garbage trucks, each lining up to dump its own load of plastics.

It doesn’t happen like this, of course, but eight million tonnes of plastic does end up in the ocean every year—the equivalent of a garbage truck’s–worth every minute. And the rate is increasing. If nothing changes, the amount of plastic sloshing around the ocean could double in 10 years. By 2050, that mass of plastic could exceed the weight of all the fish in the sea.

The good news is, compared with other industrial sources of plastic, fishing gear is fairly easy to collect or prevent from being lost. Several programs have set up free dump bins at docks to make it easier and cheaper for fishers to safely dispose of old gear. Bureo, a California-based company, buys aging nets from South American fishermen and turns them into skateboards and sunglasses. And Fishing for Litter, a program run by KIMO International, a European pollution prevention and ocean health NGO, plays to fishermen’s desire for sustainability. Since 2004, the program has encouraged commercial fishermen to gather ghost gear and other litter they find at sea and dump it in bins KIMO has set up at ports around Europe. Between 2016 and 2017, nearly 1,000 vessels gathered 470 tonnes of ocean plastics along with their catch—voluntarily.

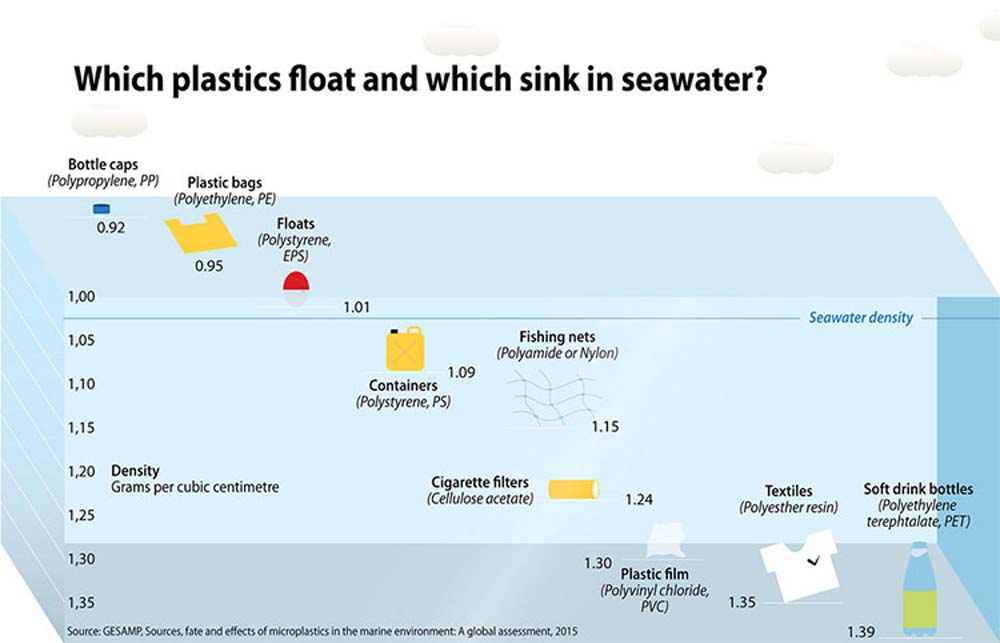

A diagram showing the density of a range of plastics, and whether they will sink or float in seawater. Credit: Grida

The costs to society and the environment are huge

A study by the consultancy firm Deloitte shows that, every year, up to 1,000,000 seabirds and 100,000 marine mammals and sea turtles die after ingesting or being entangled by plastic. Microscopic bits of plastic are working their way up the food chain, including in the seafood we eat. Plastic floating around the ocean carries invasive species that compete with or prey on native species. And when it washes onto beaches, plastic pollution affects tourism and devalues real estate. In its examination for 2018, Deloitte pegged the price of ocean plastic pollution at US $6-billion to $19-billion. That’s cheap compared with another study, which calculated the cost at up to $2.5-trillion per year, or $33,000 per tonne. None of that accounts for plastic’s costs to human health. Yet along its production cycle from oil and gas refining to use and disposal, plastic produces chemical emissions that have been linked to hormone disruption and cancer.

When exposed to sunlight, plastic breaks into smaller and smaller pieces, until they are classed as microplastics.

It’s enough to motivate teenage entrepreneurs, philanthropists, corporations, nonprofit organizations, governments, university students, and afflicted communities around the world to take action. Their ideas are seemingly as diverse as the species living in the sea: a Korean program pays fishermen to collect plastic at sea. In Baltimore, Maryland, the cartoonish Mr. Trash Wheel skims up to 17 tonnes of garbage out of the city’s harbor in a day. Inspired by the plankton-filtering ways of the whale shark, Singapore-based Drone Solutions created the WasteShark, an autonomous drone that sucks up floating bits of plastic in harbors. Chinese and Australian researchers are exploring the potential to use nanotechnology to pull microplastics out of the water in wastewater treatment facilities. Other efforts range from collecting old nets at harbors, to making plastic itself a currency to incentivize its collection, to using multimillion-dollar booms to skim plastic from the ocean’s surface, to volunteers diving to the seafloor to clean it up. There’s little doubt these efforts are well intentioned. But they are not all equal.

Almost half of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is made up of abandoned or lost fishing nets. Credit: The Ocean Cleanup

There is a harsh reality that all of us concerned with the mounting ocean plastic problem must confront:

• The vast majority of the plastic in the ocean is too small or too out of reach to ever be cleaned up. It is suspended in the water column, . . .

NOTE: Featured Image: “Ghost nets” and generally “ghost gear” also pose great danger. These are nets and lines that have torn loose and drift freely in the sea. Credit Blue Planet Archive.com