So, this is social distancing? Ah, the great outdoors. Zion National Park, Utah, this May. Bridget Bennett

Instead, increase park funding

Journalist, editor and writer focusing on the Western United States and its landscapes, communities, and cultures. Creator of Land Desk. Author of “River of Lost Souls: The Science, Politics, and Greed Behind the Gold King Mine Disaster” (Torrey House Press 2018), “Behind the Slickrock Curtain” (Lost Souls Press 2020), and the forthcoming “Sagebrush Empire: A journey into the heart of the public land wars” (Torrey House 2021). View all posts by Jonathan P. Thompson.

By Jonathan Thompson / High Country News / September 9, 2021

This story was originally published by The Land Desk and is republished here by permission.

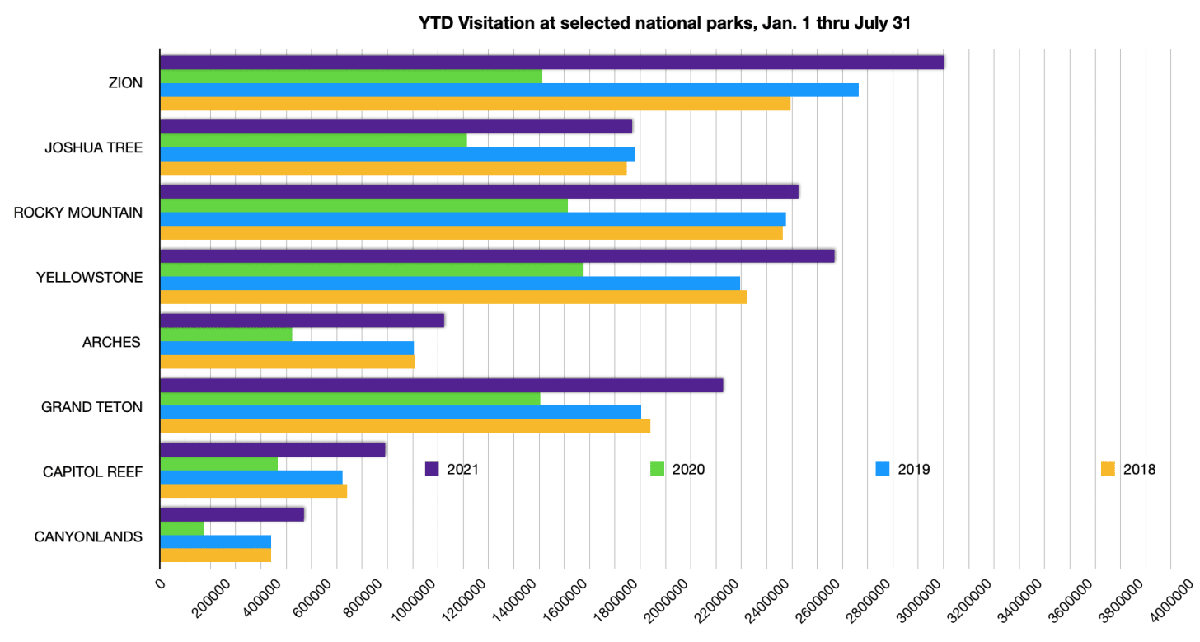

Neither the Pack Creek Fire nor two weeks of triple digit heat could keep the crowds from Arches National Park this June. A record-breaking 8,000 people per day, on average, passed through the entrance gate, overflowed the parking lots, and jammed up the trails. Nearly three times as many folks thronged Zion National Park that month, also setting a new record. The same trends were seen at Capitol Reef, Bryce Canyon and Canyonlands.

Over the last decade, crowds have inundated many of the West’s national parks. Pretty much everyone can agree on that. What to do about it — if anything — is a more contentious topic. Some National Park Service officials lean toward permitting or advance reservation systems to limit visitation numbers, while others suggest diverting visitors to less-crowded parks.

But the so-called solution drawing the most traction so far comes from Sen. Angus King (I), of Maine, who sees a simple supply-demand issue: The supply of national parks is inadequate to meet the burgeoning demand. Therefore, we should just create more national parks. This concept was fleshed out more eloquently and with a tad more nuance in a New York Times opinion piece by Albuquerque freelance journalist Kyle Paoletta, who writes:

Going to a national park in 2021 doesn’t mean losing yourself in nature. It means inching along behind a long line of minivans and R.V.s on the way to an already full parking lot. … The best way to rebalance the scale? We need more national parks.

Paoletta makes some good points. He argues that limiting visitation to a place like Arches will only push the crowds onto nearby public lands that aren’t equipped to handle them, a phenomenon we’re already witnessing. And setting aside more public lands to keep future mining claims, oil and gas drilling, and other development at bay, while providing a framework for better managing recreation and tourism on those lands, is a good idea. But turning around and designating those relatively unknown areas as national parks — thereby increasing visitation — will only bring more impacts, more infrastructure, and will do little to alleviate crowding at other parks.

Paoletta makes some good points. He argues that limiting visitation to a place like Arches will only push the crowds onto nearby public lands that aren’t equipped to handle them, a phenomenon we’re already witnessing. And setting aside more public lands to keep future mining claims, oil and gas drilling, and other development at bay, while providing a framework for better managing recreation and tourism on those lands, is a good idea. But turning around and designating those relatively unknown areas as national parks — thereby increasing visitation — will only bring more impacts, more infrastructure, and will do little to alleviate crowding at other parks.

King seems to believe that Americans are inclined to visit national parks, in general, rather than specific parks. If that were true, then every national park in the nation would be overrun with visitors. Yet Carlsbad Caverns National Park was far busier in the 1970s and 1980s than it is now, and visitation has plateaued or even declined over the past couple of decades at Chaco Culture National Historical Park and at Mesa Verde, Olympic, Petrified Forest, Guadalupe Mountains and Kings Canyon National Parks.

People keep coming to the popular places in increasing numbers despite the fact that the they could be visiting far less crowded national parks nearby. That would indicate that simply increasing the supply of national parks won’t work unless the new parks have Zion- or Grand Teton-like traits. I would argue that those places — the Ice Lake Basins or Lower Calf Creek Falls or Conundrum Hot Springs of the world — are already inundated, and designating them as national parks only would bring more hordes and more damage.

The core issue is, according to Paoletta: “There are too many people concentrated in too few places.” Perhaps this is true. But do we really want to draw people away from Zion and Arches and send them to a new Bears Ears or Natural Bridges National Park, instead? What purpose would this serve except to put too many people into more places, albeit in a less concentrated form? More importantly: Who does it serve?

Do we really want to draw people away from Zion and Arches and send them to a new Bears Ears or Natural Bridges National Park, instead?

Trash hanging from a tree (left) and a sign (right) at a popular dispersed camping area in Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton National Forest, in July 2020.

Ryan Dorgan

Certainly not the environment. The Virgin River running through Zion will be sullied whether one million or five million people walk through it each year. The alpine meadows in Grand Teton will be trampled just as ably by 3 million people as by 3.5 million people. One million people driving to Arches is going to have the same climate impact as if they were dispersed around the West. And yet, diverting just 100,000 additional people away from one of these big parks to Natural Bridges National Monument would double visitation there with serious ramifications for the monument and its ecosystems.

The main victims of national park overcrowding, it seems, are the crowds themselves — not the parks or their resources. The latter were fated to be damaged as soon as the park was designated, its associated roads and visitors centers and parking lots were constructed, and visitation hit the 500,000-per-year mark. So the main beneficiary of dispersing the Zion and Arches crowds to lesser-known monuments or parks are, again, the visitors, who may have to wait in the shuttle-line for 20 minutes instead of 30 or will have a bigger range of parking places from which to choose. That’s assuming a significant number of would-be visitors would choose to go to a new national park rather than one of the ultra-popular ones — and I’m not sure they would. Zion’s 4.5 million yearly visitors clearly aren’t afraid of overcrowding and aren’t all that interested in “losing themselves in nature.” The contrary may even be true.

With that in mind, I have an alternate proposal: Let the crowds go to Zion, Arches, Grand Teton and Yellowstone, since that’s what they want. Meanwhile, up funding for all of the parks to help mitigate damage and to control the crowds. Zion already has a shuttle system to its most popular areas to alleviate car traffic. Arches should do the same, shutting off the entire park to private, motorized vehicles and ferrying visitors via bus from Moab the park. Enact permit systems with limits for more remote, fragile areas of the parks. If park campgrounds can’t handle demand, then build more (supply and demand!) either inside or just outside the parks’ boundaries. If park staff can’t handle the numbers, then hire more people.

Meanwhile, public lands officials should work to anticipate where the disaffected parks visitors might overflow, and take preemptive measures to manage the coming crowds and stave off potential impacts. This may include administrative moves such as updating resource management plans; building new trails, campgrounds, or toilets; restricting access to sensitive areas; or higher-level actions such as designating the area as a national monument, a conservation area, a national park, or even a wilderness area — the latter two being up to Congress.

Sen. Angus says the national parks present a paradox: They’re intended to protect a place, yet they’re also supposed to provide an enjoyable experience for visitors. Maybe so, but protection should always take priority over recreation.

Fly Fishing the American River

ABOUT:

Jonathan Thompson is the editor of The Land Desk and a contributing editor at High Country News. He is the author of River of Lost Souls: The Science, Politics and Greed Behind the Gold King Mine Disaster. Email him at jonathan@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor.